Old Words, New Meanings: A Study of Trends in Science Librarian Job Ads

bbychows@indiana.edu |

cmcaffre@indiana.edu |

mccosta@indiana.edu |

angemoor@indiana.edu |

jsudhaka@indiana.edu |

yz13@indiana.edu |

Graduate Students

School of Library and Information Science

Indiana University

Bloomington, Indiana

Abstract

Job ads are supposed to provide careful descriptions of the positions being advertised. Based on this premise, an analysis of job ads over time should reveal emerging trends and changes in a profession. The existing literature on science librarianship emphasizes that there are fluctuations in the demand for subject expertise and technology skills at different periods of time. After gathering job ads from the beginning and end of a ten-year period, a close reading of the ads revealed surprisingly few changes in the requirements for science librarian positions. This suggests that what employers are looking for has not changed in spite of the changes in the profession. This analysis also points to a set of core qualities in the profession, though what the qualities mean could have changed over time. This study explores the data gathered from the collected ads and offers some explanations for the results.

Introduction

Within the library science world, librarians increasingly claim that technological advances are changing the very nature of library professions. Since a wealth of information is available online, extensive physical collections are sometimes viewed as less essential than they previously were. Furthermore, some information seekers no longer find it necessary to visit libraries or speak to library professionals.

This transformation of the profession is troubling news to many librarians. Changes in the borrowing and visiting habits of patrons can lead to the downsizing of library collections and staff or the total elimination of entire libraries. Even if the library is safe, some librarians balk at the idea of changed perceptions of their positions; they do not wish to be seen in a purely technology-oriented manner.

Additionally, any changes in the profession should be reflected in changes in education and training (DeArmond, et al. 2009). If new or different skills are being required of librarians, then library schools should adjust their curricula to adequately prepare the next generation of librarians for the new library environment.

Concerns such as these motivated this study. The authors wished to learn if the science library profession has changed over time and, if it has, whether the changes reflect a modification of the core competencies of librarianship or if these changes are more marginal. This study chose to look specifically at academic library positions within the sciences, because there seems to be a greater similarity across the needs of academic institutions than might be found in a corporate setting.

Well-written advertisements for job openings ought to add insight to the open position and its working environment. A good advertisement highlights the most essential information candidates need to know before applying, such as the core values of the institution, the basic requirements of the profession, major responsibilities of the position, and the skills needed to perform the required duties. Therefore, by comparing job advertisements over time, changes in the profession should become apparent.

This study looks at job advertisements, specifically the required and recommended skills and experiences, for various types of academic science librarian positions from 1998-2001 and compares them to similar job advertisements from 2008-2010. It examines how the requirements and recommended skills for science librarian positions have changed over the past decade and makes explicit the changes in the qualifications most recommended and required now compared to those from ten years ago, and proposes explanations for these changes.

Background

In recent years, there have been many articles and studies about the changing nature of science librarianship and the shifting of qualifications for science librarians (Lucker 1998; Ortega and Brown 2005; Osorio 1999). These studies have focused on the analysis of job ads and interviews with professionals in the field. The findings of these studies, derived from the examination of current librarians, as well as evidence of what institutions are looking for in new recruits, have been used to shape an image of the current state of science librarianship, including an increase in job responsibilities and a decrease in required subject expertise.

Ortega and Brown (2005) surveyed members of discussion groups that were connected to physical science librarianship and found that 63% of respondents had majored in science as undergraduates, 18% had a master's degree in science, and 96% had earned a MLS or MLIS. While Ortega and Brown focused on physical science librarians, their findings support Lucker's (1998) statement about the importance of a science background. The survey also found that a large number of physical science librarians had over 11 years of experience in the profession and that their impending retirement will create greater opportunities for those interested in and prepared for the field of physical science librarianship.

A study by Wu and Li (2008) analyzed job announcements to identify responsibilities and qualifications in the field of health science reference librarianship. The results of their study show that a relevant subject background was desired in 50% of ads and that the most frequently mentioned qualification was excellent oral and written communication skills (Wu & Li 2008). 60% of the job announcements did not require previous work experience which shows an opportunity for new MLS graduates (Wu & Li 2008).

Similarly, Osorio (1999) studied job descriptions of science-engineering librarian positions to analyze how qualifications and responsibilities changed over time. Job ads from 1976, 1986, and 1998 were examined in an effort to explore the changes across that time span (Osorio 1999). Osorio gathered key terms from each group of job descriptions and then compared each year's term list. Results of the study found that there was an increase in descriptors in the job ads over time (Osorio 1999).

Despite many studies confirming the necessity of an academic science background both Brown (2007) and Level and Blair (2007) commented on the perceived shortage of qualified science librarians who have an academic science background. This shortage means that the responsibilities and qualifications of a science librarian are rapidly changing. One change Brown noted after conducting a survey of job advertisements from 2005 and 2006 is that the qualification of academic science knowledge or equivalent experience in a science library is shifting from a required qualification to a preferred one.

A recent study by Meier (2010) discovered that science librarian positions from 2008 and 2009 have an increased demand in responsibilities that positions in the 1980s did not. The average job ad analyzed listed nearly 16 duties, up from an average of five. Meier noted that job titles are significantly more complex, reflecting an emergence of combination jobs. The study found that out of 55 job postings, there were 45 unique position titles. In combination with Jones et al. (2002), Meier's study points to a more generalized approach to science librarianship.

Similarly, DeArmond et al. (2009) found that the most desired qualifications in job postings for science librarian positions from 2009 were an ALA accredited MLS/MIS/MLIS degree, customer service experience, communication skills, and instruction experience. After those qualifications, a science background, gained either though academic training or experience, was desired. Subject experience was less emphasized in jobs that were general liaison positions to the sciences. Unsurprisingly, this study concluded that innovative technological skills were required in the minority of job positions agreeing with other studies such as Matthews and Pardue (2009) which found web development experience to be demanded in approximately 30% of job advertisements.

These studies have shown that some changes have occurred in the qualifications needed for the profession over recent years in the field of science librarianship. However, each of these studies has focused on a particular subsection of science, and the present study will focus on academic librarian job announcements in the fields of physics, chemistry, health and life sciences, geological sciences, and general science, drawing conclusions about the field as a whole. In addition, the majority of these previous studies have focused on the importance or perceived importance of having subject-specific knowledge, and have not examined all of the qualifications being asked for, not just those relating to subject experience. The present study will investigate what, if any, changes have occurred in the broad field of science librarianship over the course of a decade, taking an inclusive view of the range of qualifications and experiences that appear in job ads for science librarians.

Methods

The authors analyzed the content of 64 job advertisements from 1998-2001 and from 2008-2010 to determine what qualifications are required or desired for science librarian positions. Specific qualifications were first tabulated by subject. Frequencies of each qualification were then aggregated across all the subjects.

The authors gathered job advertisements from online sources, mainly mailing list archives of academic institutions and Special Library Association (SLA) divisions. On mailing list sites, job postings could were retrieved by keywords and posting time. Useful keywords included "vacancy," "position," "job," "opening," and subject names, such as biology, chemistry, physics, etc. Job postings were collected and sorted and sorted into five classes or subject areas: General Science, Chemistry, Biology/Health Science, Geosciences and Geographic Information Systems, and Physics. The job advertisements were restricted to those from colleges and universities with graduate programs in the subject being investigated, since the qualifications for science librarians differed between academic and corporate libraries. Geographic areas of job advertisements were limited to the United States and Canada.

Initially, the authors planned to access job postings from three time points, 1999, 2004 and 2009. Three to five postings per subject per year were sought. However, for some subjects, it was difficult to find three to five postings in a particular year, so job advertisements from two time spans, from 1998-2001 and 2008-2010, were gathered. Thirty-three (1998-2001) and 31 (2008-2010) postings were collected, respectively.

After the job advertisements were gathered, they were coded based on the skills or knowledge that was required or desired using a coding scheme containing 32 variables created by DeArmond et al. (2009). Job postings were first coded and analyzed within their respective subjects. The data from each subject were then aggregated and analyzed to generate overall statistics describing the change in qualifications for science librarians over time. The frequency with which each variable occurred was calculated and represented as a percentage.

Results

The results of this study challenge the literature that claims that there have been significant changes in required and recommended qualifications for science librarian jobs. While there have been changes in the required qualifications, the most notable being a 14% decline in customer service/peer relations, none were large enough to be considered statistically significant. This may be because the sample represents only a small percentage of job postings available during these time periods.

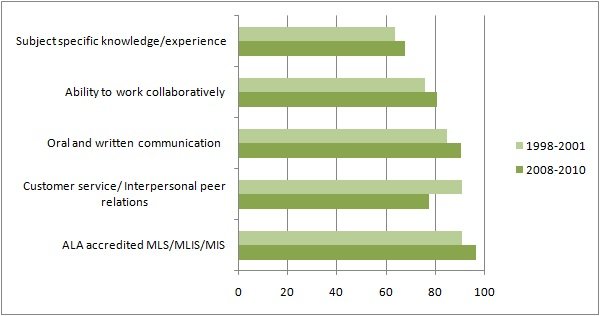

As illustrated in Figure 1, the data show that little has changed in the required qualifications over the two time periods that were examined. The data range from a four percentage-point increase in subject-specific knowledge (64% to 68% of job postings) to a 14 percentage point decrease in customer service/interpersonal peer relations (91% to 77% of job postings). Oral and written communication skills and the ability to work collaboratively both increased five percentage points from the first time period to the second time period (85% to 90% and 76% to 81% of job postings, respectively). The requirement of an ALA-accredited MLS, MIS or MLIS increased six percentage points from (91% to 97% of job postings).

T-tests were run on the data for these subjects to determine whether the changes were significant. The subject with the greatest percentage of change, customer service/interpersonal peer relations, had the highest t-score at 1.809, which with p<.05, was less than the t-critical value of 1.8595, demonstrating that the change was not statistically significant. As the other four qualifications had t-scores equaling 0, their changes were not statistically significant, either.

Figure 1

Top 5 Required Qualifications 1998-2001 and 2008-2010

The recommended qualifications show an interesting trend. Four of the top seven recommended qualifications from 1998-2001 declined in frequency in job postings in 2008-2010. Furthermore, six of the seven top recommended qualifications for 2008-2010 showed an increase in frequency in postings from 1998-2001.

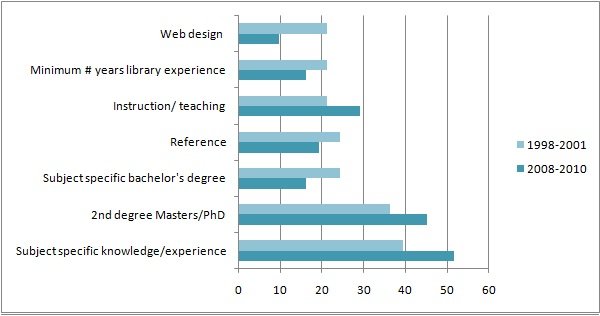

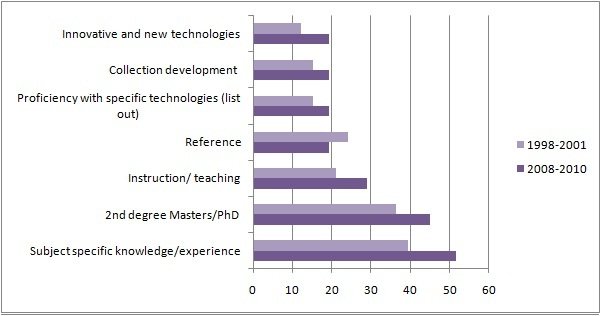

Figure 2 shows the top seven recommended qualifications from 1998-2001, with their percentages from both 1998-2001 and 2008-2010. Figure 3 shows the top seven recommended qualifications from 2008-2010, also showing the percentages from both time spans. Four qualifications were shared between both lists: subject specific knowledge/experience, second Master's degree or Ph.D., reference experience, and instruction experience.

As Figures 2 and 3 show, there is a 13 percentage point increase (39% to 52% of the postings) in the recommendation of subject specific knowledge/experience, which is larger than the four percentage point increase in job ads requiring subject-specific knowledge/experience. The recommendation of a second Master's degree or Ph.D. increased nine percentage points (36% to 45%). Reference experience actually decreased five percentage point (24% to 19%) from the first to second periods to time whereas instruction and teaching experience increased eight percentage points (21% to 29%). None of these data were statistically significant either, with the highest t-score (subject specific knowledge/experience) at t=0.7171, with p<.05 and t-critical=1.8595.

Figure 2 also shows declines in other recommendations between the two time periods. A recommended subject-specific bachelor's degree declined by eight percentage points (24% to 16%) between the first and second time periods. The recommendation of a minimum number of years of library experience declined five percentage points (21% to 16%). Web design experienced the greatest decline at 11 percentage points (21% to 10%) between the two time periods, though with t=1.7056, p<.05 and t-critical=1.8595, this was not statistically significant either.

Figure 3 shows mostly increases in recommended qualifications although these were small increases. Proficiency with specific technologies and collection development experience both increased by four percentage points (15% to 19%). Innovative and new technologies increased seven percentage points (12% to 19%), which are smaller than changes seen elsewhere.

Figure 2

Top 7 Recommended Qualifications in 1998-2001, compared with percentages in 2008-2010

Figure 3

Top 7 Recommended Qualifications in 2008-2010, compared with percentages in 1998-2001

Discussion

The literature on job ads for science librarians argues that there have been many changes in the profession and in requirements for job applicants over the years. However, the job ads gathered and examined here would seem to suggest otherwise. The top five required qualifications found in the job ads remained the same from 1998 to 2010. Though the percentage of ads including these requirements did change (going up for four and going down for one), none of these changes represented a statistically significant difference. Four recommended qualifications appeared in the top seven for both time periods suggesting some stability, though the other three qualifications listed were quite different.

As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the list of the seven most recommended qualifications changed between 1998 and 2010. Having subject-specific knowledge or experience, a second Master's degree or PhD, experience with instruction or teaching, and reference experience were in the top seven for both time ranges. However, a subject-specific Bachelor's degree, a minimum number of years of library experience, and web design were replaced in importance by proficiency with specific technologies, collection development, and innovative and new technologies. Again, however, none of the changes were statistically significant. This implies that, though science librarianship itself may have changed, the qualities expected in job applicants have not. One of the surprises here was that the recommendation of web design decreased so much and dropped off of the list. Though not a significant change, it is still interesting to note. It seems possible that there are so many off the shelf or ready-made web templates available these days that require low expertise for maintenance, the necessity for experience in this area decreased.

The job ads looked at spanned the field of science librarianship, including ads for general science librarians, as well as field-specific librarians in biology/health science, chemistry, physical sciences, and geosciences. This means that desire for these qualities is shared among all of these fields, hinting at an underlying consensus among all science librarians about what the core qualifications for their type of librarianship are, and that these core qualities are not field specific.

Advancements in technology and library automation have dramatically changed the face of librarianship over the past decade. Yet the qualities asked for by employers have not changed significantly, pointing to stability in the profession that has survived all of the changes. The core qualifications of the profession, as shown by the consistent top five required qualifications found in this study, do not relate to anything as transient as technology. Perhaps this is not just because the profession has the same values as it did ten years ago. It could also indicate that these qualities have come to mean new things, have been adapted to suit the times. Yes, an ALA-accredited Master's degree is still essential, but a modern Master's education is different than it was a decade ago, which was different from the decade previous. This adaptability and emphasis on a stable core of qualities bodes well for the profession's ability to survive the changes in technology and information occurring now and that will continue in the future.

The qualifications consistently sought in job advertisements are centered on a basic grounding in library science and good people skills. It would seem that employers realize that good librarianship is, at its heart, about working well with clients and peers. All of the science knowledge in the world will not help a librarian if she cannot effectively help others find information or clearly communicate with them.

There are, however, other possible explanations for the study's results. One, based on the assumption of the profession remaining unchanged in many ways, is that employers are not adapting the vocabulary and terminology of their advertisements to suit the needs they truly have. With trends toward integrating information literacy into classroom curricula, does the need for a librarian experienced in "instruction" mean what it used to? Are today's reference needs what they used to be? Perhaps employers need to re-evaluate the writing of job ads, paying particular attention to updating the descriptions of what they are seeking.

A second possibility is that the earlier of the two time periods looked at (1998-2001) came after major upheaval caused by a technology boom. These results could point to the profession having reached a state of equilibrium after a major change, rather than it maintaining a solid core during any fluctuation. Supporting or rejecting this proposition would require research into when technology most influenced the library profession, or even if that influence was confined to a specific period of time.

Though librarianship has changed dramatically in the past decades, certain core qualities of librarianship, specifically those embodied in science librarians, have remained constant. As only the last of the top five required qualities (subject-specific knowledge and experience) specifically relates to being a science librarian, it would be interesting to examine the job postings for a variety of different types of librarians and see if those top four requirements (ALA-accredited MLS/MLIS/MIS, customer service/interpersonal peer relations, oral and written communication, and ability to work collaboratively) would be equally as important in other types of librarianship.

Another area deserving research attention is the duties and responsibilities of science librarian positions and their change over time. This study simply examined the qualifications asked for in job advertisements. The literature points to a change in the responsibilities listed in job ads. Perhaps the changes in responsibilities should be tracked alongside changes (or lack thereof) in the qualifications looked for in applicants. Do the two change together, or does one stay the same while the other changes? Such research could help explain any simultaneous change and stability in the profession.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Brian Winterman for his guidance and advice during all the stages of the preparation of this paper. We would also like to thank Howard Rosenbaum for his editorial assistance on the writing of this paper.

References

Brown, C. 2007. Recruiting the best. Science & Technology Libraries 27(1-2): 41-53.

DeArmond, A.R., Oster, A.D., Overhauser, E.A., Palos, M.K., Powell, S.M., Sago, K.K., & Schelling, L.R. 2009. Preparing science librarians for success: an evaluation of position advertisements and recommendations for library science curricula. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship [Internet]. [Cited September 2, 2010]; 59. Available from: http://www.istl.org/09-fall/article1.html

Jones, M.L.B., Lembo, M.F., & Manasco, J.E. 2002. Recruiting entry-level sci-tech librarians: an analysis of job advertisements and outcome of searches. Sci-Tech News 56(2): 12-16.

Level, A.V. & Blair, J. 2007. Holding on to our own: factors affecting the recruitment and retention of science librarians. Science & Technology Libraries 27(1-2):185-202.

Lucker, J. 1998. The changing nature of scientific and technical librarianship: a personal perspective over 40 years. Science & Technology Libraries 17(2), 3-10.

Mathews, J.M. & Pardue, H. 2009. The presence of IT skill sets in librarian position announcements. College & Research Libraries 70(3):250-257.

Meier, J.J. 2010. Are today's science and technology librarians being overtasked? An analysis of job responsibilities in recent advertisements on the ALA JobLIST web site. Science & Technology Libraries 29(1-2):165-175.

Ortega, L. & Brown, C.M. 2005. The face of 21st century physical science librarianship. Science & Technology Libraries 26(2): 71-90.

Osorio, N.L. 1999. An analysis of science-engineering academic library positions in the last three decades. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship [Internet]. [Cited September 2, 2010]; 24. Available from: http://www.istl.org/99-fall/article2.html

Wu, L. & Li, P. 2008. What do they want? a content analysis of Medical Library Association reference job announcements, 2000-2005. Journal of the Medical Library Association 96(4): 378-381.

| Previous | Contents | Next |