Trends in the Use of Supplementary Materials in Environmental Science Journals

Jeremy Kenyon

Natural Resources Librarian

jkenyon@uidaho.edu

Nancy R. Sprague

Science Librarian

nsprague@uidaho.edu

University of Idaho Library

Moscow, Idaho

Abstract

Our research examined the use of supplementary materials in six environmental science disciplines: atmospheric sciences, biology, fisheries, forestry, geology, and plant sciences. Ten key journals were selected from each of these disciplines and the number of supplementary materials, such as data files or videos, in each issue was noted over a period of 12 years. A significant rise in the use of supplementary materials was observed for all six subject areas for the study period. Publisher's policies about supplementary materials were also investigated. We analyzed trends in the use of supplementary materials to better support the researchers we work with in these subject areas and to identify ways that librarians can help ensure continued access to these research materials.

Introduction

Methods for communicating research and results in the environmental sciences are changing. One change is a notable increase in the number of online articles that include supplemental material. Very little research has been done to examine this trend. Supplementary materials go by myriad terms: supplemental materials, supplemental data, auxiliary information, supporting information, and supplementary content. They may include videos, audio files, high resolution imagery, extended statistical analyses, and expanded explanations of methods.

Often, supplementary materials are being provided by authors in order to augment and expand the traditional research article, either by their own desire, or by request of reviewers (Borowski 2011). However, there has been limited discussion of this change except in a few circles, such as among scientific publishing observers and through the National information Standards Organization (NISO/NFAIS 2013).

This study presents an investigation into 60 scientific journals in six subject areas in the environmental sciences to identify how the inclusion of supplementary materials changed between 2000 and 2011. Our definition of environmental sciences is rather broad and includes the following disciplines that fall within the College of Natural Resources and the College of Science at the University of Idaho: atmospheric sciences, biology, fisheries, forestry, geology, and plant sciences. We examine journal policies to clarify the approach taken by various publishers and journals regarding the role of these materials and how they are made accessible for users.

Our study focused on supplementary material directly linked to the journal article itself within the context of its publisher's web site. In the case of the Geological Society of America's journals, there is an external publisher repository for supplementary materials of its publications, and each entry in the repository is associated with its corresponding publication. In this case, we used this repository to identify supplementary material data.

Links to supplementary materials are often provided from the journal's table of contents. In other cases, links or references to the supplements are embedded within the text of the article. Figure 1 shows an example of what an end-user encounters, which is the object of this study.

Figure 1. Supplementary Material Link Example

Literature Review

Few recent studies have investigated the significant rise in the numbers of supplementary materials included in science journals and the challenges this trend has created. Schaffer and Jackson (2004) focused on the use of supplemental data in journals from a range of science disciplines, including astronomy, chemistry, mathematics, molecular biology, and physics. They noted dramatic increases in the numbers of publishers allowing researchers to include supplementary data and predicted that this trend would continue at a rapid pace. Supplementary materials were allowed in 69% of the journals they examined in 2004. They recommended several topics for further research, including access issues, archiving practices, and editorial review policies for these materials.

Editors of several key science journals have expressed concerns about the rapid increase in supplementary materials and the potential implications for authors, reviewers, and readers. Marcus (2009), editor of Cell, stressed the need for more consistency in the way these supplemental materials are handled. She also described new guidelines for ensuring that only supplemental data that directly support a specific figure or table in an article will be included in Cell. Maunsell (2010) explained why the Journal of Neuroscience would no longer accept supplemental materials, in part due to their perceived adverse effects on the journal's peer-review process. He cautioned that the growing volume of supplemental materials was making it difficult for reviewers to put sufficient time and effort into reviewing these materials closely, resulting in inadequate reviews or potentially reducing the scrutiny of the rest of the article. Maunsell also discussed the potential for supplemental materials to undermine the idea of a self-contained research article by providing a place where essential information, such as methods, could be lost. In contrast, editorials in Science (Hanson et al. 2011)and other major science journals have expressed support for the use of supplementary materials and strongly encouraged researchers to submit them with their articles.

Anderson et al. (2006) raised concerns about long-term, consistent access to supplementary materials. In their study of biomedical journals covering the period 1998-2005, they found that only 74% of articles had links to supplemental data that were still accessible and that data stored on a publisher's web site had a significantly higher probability of being persistent than data linked from an author's web site. They recommended that maintaining long-term access to supplemental materials be given a higher priority by publishers, granting agencies, and researchers. Williams (2013) discovered supplementary files that were missing from a publisher's web site and discussed this issue in her interviews with crop science researchers concerning data sharing options. She also learned that researchers occasionally had difficulties reusing data from supplemental materials because these data were not well described or did not follow established standards.

Schwarzman's (2009) survey of publishers' practices regarding supplementary materials generated interest in clarifying the role of these materials and how they are handled. In January 2010, his survey was followed up by a Roundtable on Best Practices for Supplemental Journal Article Materials, co-sponsored by the National Information Standards Organization (NISO) and the National Federation of Advanced Information Services (NFAIS). This meeting discussed the need for more standardized publishing policies for supplemental materials and set up two working groups to address both business practices and technical issues.

Recent efforts to develop recommended practices for incorporating supplemental materials into the publication process in a more consistent way are described by Beebe (2010), Carpenter (2009; 2010a; 2010b), Laue (2010), Rosenthal and Reich (2010), and Smit (2011). Draft recommendations related to supplementary materials were released by the NISO/NFAIS working groups for comment in 2012 and the Recommended Practices for Supplemental Online Journal Articles were approved and published in January, 2013 (NISO/NFAIS 2013). These best practices provide valuable guidance for publishers, authors, peer reviewers, and librarians on issues such as ensuring discoverability and findability, providing good metadata, assigning persistent identifiers, archiving, referencing, and migration of supplemental materials to maintain future access.

Potential roles that librarians can play in ensuring access to supplemental data are addressed by Lorbeer & Klusendorf (2010). They envision librarians as "gatekeepers who can help to preserve, protect, and make available supplemental data" by tagging metadata so these data can be more easily searched by researchers, providing expertise on copyright and long-term preservation issues, and storing these data in institutional repositories when appropriate. Our study was designed to investigate trends in the use of supplementary materials in environmental science disciplines to better support the researchers we work with in these subject areas.

Methods

Subject Selection

We selected subject areas which fit our collection management responsibilities at the University of Idaho. These include atmospheric sciences (including meteorology), biology, fisheries (and aquatic biology), forestry, geology, and plant sciences (or botany). We sought to exclude microbiology, biochemistry, and similar fields in order to differentiate our findings from the Schaffer and Jackson (2004) previous study. However, some of the biology journals that we examined have multidisciplinary content and some overlap is inevitable and acceptable. Further, we see a tandem growth in environmental research output and in data sharing initiatives. Supplementary materials can play a role in sharing data.

Journal Selection

We began by selecting the twenty most prominent journals in the identified subject areas using Thomson Reuters' Journal Citation Reports (JCR) database. The JCR categories used were: 1) Meteorology & Atmospheric Sciences, 2) Biology, 3) Fisheries, 4) Forestry, 5) Geology and Geosciences, Multidisciplinary (two categories combined), and 6) Plant Sciences. The journals were ranked in each area according to three schemes: the traditional two-year Journal Impact Factor, the Eigenfactor Score (five year) and the Article Influence Score (five year). Each journal was given a simple numerical score (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) based on its rankings in each scheme. For example, the top-ranked journal received a score of 1, the second-ranked journal received a score of 2, and the seventh-ranked journal received a score of 7. No weighting was used as we considered the three rankings schemes to be independent from each other and viewed them collectively as three different perspectives on the journals' importance, even though these factors have been found to be strongly correlated (Davis 2006). As each journal was given three scores, the final ranking was a sum of those three scores, where the top rank was decided by the lowest overall score.

A secondary goal for the selection of journals was to obtain a diversity of publishers. The purpose was to examine the different treatments of supplementary materials by different publishers, including the guidelines and policies -- or lack thereof -- as applied to these items. The authors set a limit of two journals in each category that could belong to the same publisher. In some fields, publishers such as Wiley-Blackwell or Elsevier were dominant, representing as many as four or five of the top 10. In all cases, the authors simply selected the next highest ranked journal with a different publisher. The journal rankings both before and after the publisher filtering are provided here as supplementary material (Appendix 1).

The final result is a journal list of 60 titles, with 10 journals from six different subject areas (Table 1). It contains many of the major journals in each of the fields listed, with a few titles that may not hold that status in the eyes of some of the field's practitioners, due to the goal of diversity in publishers. We acknowledge that some environmental science titles, such as those from the Ecological Society of America, may seem to be missing from our sample. This category was not included in our initial selection process, and therefore, did not appear on our lists.

Table 1. Journals Selected for Inclusion in this Study

Subject |

Journal Name |

Publisher |

|

Atmospheric Sciences |

Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics |

European Geosciences Union/Copernicus |

|

Atmospheric Environment |

Elsevier |

||

Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society |

American Meteorological Society |

||

Climate Dynamics |

Springer |

||

Climatic Change |

Springer |

||

Environmental Research Letters |

Institute of Physics |

||

Global Biogeochemical Cycles |

American Geophysical Union |

||

Journal of Climate |

American Meteorological Society |

||

Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society |

Wiley-Blackwell |

||

Tellus Series B |

Co-Action |

||

Biology |

BioEssays |

Wiley-Blackwell |

|

Biological Reviews |

Wiley-Blackwell/Cambridge Philosophical Society |

||

BioScience |

American Institute of Biological Sciences |

||

BMC Biology |

BioMed Central |

||

FASEB Journal |

Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology |

||

Journal of Experimental Biology |

Company of Biologists |

||

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B - Biological Sciences |

Royal Society |

||

PLoS Biology |

Public Library of Science |

||

PLoS One |

Public Library of Science |

||

Proceedings of the Royal Society B - Biological Sciences |

Royal Society |

||

Fisheries |

Aquaculture |

Elsevier |

|

Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences |

NRC Research Press |

||

Diseases of Aquatic Organisms |

Inter-Research |

||

Fish and Fisheries |

Wiley-Blackwell |

||

Fish and Shellfish Immunology |

Elsevier |

||

Fisheries |

Taylor & Francis/American Fisheries Society |

||

Fisheries Oceanography |

Wiley-Blackwell |

||

ICES Journal of Marine Science |

Oxford University Press |

||

Marine and Freshwater Research |

CSIRO |

||

Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries |

Springer |

||

Forestry |

Agricultural and Forest Meteorology |

Elsevier |

|

Annals of Forest Science |

EDP Sciences (Springer after 2011) |

||

Applied Vegetation Science |

Wiley-Blackwell |

||

Canadian Journal of Forest Research |

NRC Research Press |

||

Forest Ecology and Management |

Elsevier |

||

International Journal of Wildland Fire |

CSIRO |

||

Journal of Vegetation Science |

Wiley-Blackwell |

||

Plant Ecology |

Springer |

||

Tree Genetics & Genomes |

Springer |

||

Tree Physiology |

Oxford University Press |

||

Geology |

Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences |

Annual Reviews |

|

Biogeochemistry |

Springer |

||

Biogeosciences |

European Geosciences Union/Copernicus |

||

Earth-Science Reviews |

Elsevier |

||

Geological Society of America Bulletin |

Geological Society of America |

||

Geology |

Geological Society of America |

||

Geophysical Research Letters |

American Geophysical Union/Wiley-Blackwell |

||

Nature Geoscience |

Nature |

||

Paleoceanography |

American Geophysical Union/Wiley-Blackwell |

||

Quaternary Science Reviews |

Elsevier |

||

Plant Sciences |

Annual Review of Phytopathology |

Annual Reviews |

|

Annual Review of Plant Biology |

Annual Reviews |

||

Current Opinion in Plant Biology |

Elsevier/Current Biology |

||

Journal of Experimental Botany |

Oxford University Press |

||

Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions |

American Phytopathological Society |

||

New Phytologist |

Wiley-Blackwell |

||

Plant Cell |

American Society of Plant Biologists |

||

Plant Journal |

Wiley-Blackwell |

||

Plant Physiology |

American Society of Plant Biologists |

||

Trends in Plant Science |

Elsevier |

||

Data Collection

We counted the number of articles with supplementary materials in every issue of the selected journals for the period 2000-2011. Each author reviewed five of the ten journals for each of the six subjects via their publishers' web sites. In one case, the journal publisher used JSTOR's Current Scholarship program to provide access to their materials. These articles did have supplementary materials links. To measure overall journal output, we used the Journal Citation Reports' citable documents measure for each year of the journal. This variable defines the only citable documents of a journal to be research articles, reviews, and notes (Moed 2005), all of which constitute the majority of journal items in which supplementary material is associated. Further, it is a widely accessible variable that provided a standardized measure upon which to measure the percentage of articles with supplemental material.

In summary, the data that we gathered were the number of journal items that contained supplementary material per issue and the number of citable documents per year. Ancillary information, such as the volume and issue number and year were also recorded. Lastly, we observed the types, formats, and sizes of supplemental data, but can present no definitive trends for those areas, merely observations at this point. A future study is planned to analyze this content formally across our selection of journals.

Limitations

This study contains three significant limitations. First, it is observational and can only present speculation on the causal factors for why the trends occurred the way they have. In the course of our discussion, we will highlight areas of discrepancy or curiosity, all of which point to future areas of study and potential avenues of investigation. Second, the selection of journals is not an appropriate sample to interpolate those results against the entire population of journals in the environmental sciences. Instead, these results display trends in many widely read and highly cited journals, which may in turn have an impact on scholarly communication in these fields. Third, to increase publisher diversity when compiling our journal lists, we found it necessary to skip a few highly-ranked journals. There was no impact on the top eight titles for all the subjects, and in most cases nine out of the top ten titles were included in our selection process.

Results

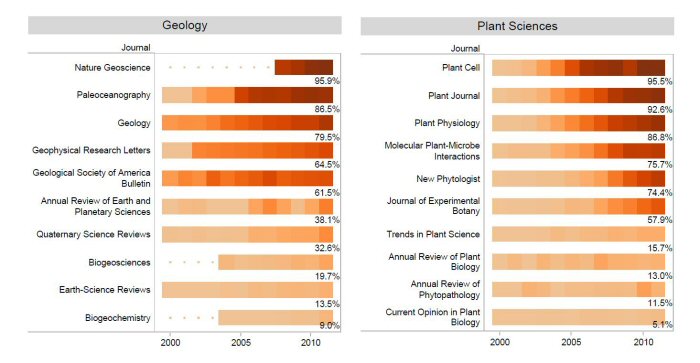

Figure 2 illustrates the trends in the use of supplemental materials for each observed journal. Each row shows the yearly percentage rates of articles with supplementary materials for a journal, grouped by subject. There is a clear and accelerating trend of increased use of supplementary materials across different subject areas. For those journals whose publication preceded 2000, few had any articles with supplemental data during that year. Only our geology sample had any journals with rates over 20%. Biology and fisheries each had one journal with less than 10%. However, by 2011, only one journal, Fisheries, did not contain supplementary material. All other 59 journals contained some. In several cases, over 90% of articles contained supplementary materials. Underlying data for Figure 2 are listed in Appendix 2.

Figure 2. The percentage of articles with supplementary materials by journal.

Comparison Between Subjects

Biology, plant science, and geology contained the most supplementary materials, each with a median percentage of over 40% in 2011. These top subject areas each had at least five journals with more than 50% of their articles containing supplementary material by 2011. In fact, these journals have been at this rate for several years. In some fields, such as fisheries, the percentage of articles with supplementary materials is low and has only very recently changed. In others, there is a long pattern of growth for more than a decade. These variations suggest a number of investigations need to be carried out to further understand the individual dynamics of supplementary material use and practice.

Certainly variations between subjects are, at least partially, a product of the way the journals are classified into these six categories. Some of the journals could be classified in multiple categories -- Agricultural and Forest Meteorology appears in both Atmospheric Sciences and Forestry, for example -- and the effects of re-classifying the journals would make the categorical differences change. But classification does not explain the entirety of the differences. Very few journal articles in fisheries journals contain supplementary materials. Most plant sciences journal articles do. Why such an extreme difference? Further study into author behaviors -- why authors choose to publish in certain journals and why they provide supplementary materials -- is needed. Are there social incentives or disincentives common with these research communities? Or is it individual author choice? Lastly, further study into use of supplementary materials would help clarify the dynamics of demand, a much needed perspective given the increasing supply evident in our results.

Comparing Fine vs. Coarse Scale Research Methods

Another curious trend seen across this study is the variation between journals that commonly present research which uses fine scale research methods to those that present coarser methods. Scale is a geographic concept that describes the granularity of an area of study. Finer scales cover a small or minute physical space. Coarse scales cover a wider area. This concept proves useful in considering how research methods can focus on analysis on the microscopic scale or the global scale. Fine scale methods, used in genetics or microbiology are typically data-intensive and are clearly among the early adopters of supplementary materials as a norm. Editorials discussing the use of supplementary materials have been more common in journals that deal with these subjects than others, such as Cell and the Journal of Neuroscience (for examples see Marcus 2009; Maunsell 2010; Borowski 2011). Coarser methods, such as in climate modeling or working with land cover data (i.e., satellite or airborne LiDAR), as data-intensive as they are, have been much slower to use supplementary material.

This contrast appears to play out in our forestry journals, where the Journal of Vegetation Science and Tree Genetics and Genomes possess supplementary materials at a rate much higher than others. Journals such as Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, or the International Journal of Wildland Fire, where it is more common to see articles with coarser methods in use, appear to have extremely low levels of supplementary material use. This distinction may be tied to other factors, e.g., the size or complexity of coarse, gridded data sets being too much for any meaningful data distribution, or other factors, such as the lack of a centralized publication and data sharing (e.g. NCBI/Pubmed) infrastructure for these fields that may encourage a culture of sharing. In either case, the relationship between methods and the use of supplementary materials merits further investigation.

Differences Among Journals

A noticeable difference also exists between primary literature journals -- those that publish the output of new research -- and secondary literature journals -- those that publish reviews, meta-analyses, and similar cumulative scientific work. Clearly, secondary literature journals provide supplementary information at a much lower rate of than primary literature journals. Examples include the Annual Reviews titles, Current Opinion in Biology, and Trends in Plant Science. There is also variation within these individual journals. The Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Science, for example, varies widely from year to year, but in some years, has a nearly 30% inclusion of supplementary materials with its articles.

It should be noted as well that several journals contain "short communications" as a part of their issues, including the International Journal of Climatology, which has one of the lowest percentages of supplemental materials. In contrast, Environmental Research Letters, an entire journal devoted to short communications, has relatively high levels of supplementary material.

A final note is that journals created since 2000, such as PLoS Biology or Nature Geoscience, have shown to have very high levels of supplementary materials since inception. Only Biogeosciences and Biogeochemistry appear to follow the pattern of older journals. These newer journals -- many of them fully open access -- have begun with the option of including supplementary materials from the very beginning, and manage to exceed nearly all others in disseminating supplementary material. These newer journals also have detailed publisher policies encouraging researchers to provide supporting information, so we observed that there may be a relationship between supportive publisher's policies and the increased use of supplemental materials. Additional observations about current publisher policies are presented below.

Publisher and Journal Policies Regarding Supplementary Materials

Aside from the variations between subjects, methods and journals, publisher and journal policies regarding supplementary materials varied widely. A comparison of selected features of these policies, including peer review, metadata, and recommended file formats and file sizes, is presented in Table 2. Links to the policies and author guidelines for each of the journals in our study are provided in Appendix 3. Some publishers, such as Annual Reviews, provided general guidelines for supplementary materials that apply to all of their journals. With other publishers, such as Elsevier, specific guidelines were provided for each individual journal, although the general policies tended to be consistent for each publisher, with slight variations to meet the needs of different disciplines. For journals such as Geophysical Research Letters, which is published by Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the American Geophysical Union (AGU), we listed both publishers and identified the publisher responsible for the guidelines on supplementary materials.

In most cases the policies regarding supplementary materials were found within the "Instructions for Authors" section on the journal's web site, but they were sometimes difficult to locate or scattered in several different locations. One of the challenges in locating the guidelines was the variety of terms used by publishers to describe supplementary materials, including auxiliary materials, data supplements, supporting information, or supplemental content.

Some publishers, such as AGU, Nature Publishing Group, and Wiley-Blackwell, strongly encouraged the use of supplementary materials in their journals and provided extensive justifications and instructions for their use. Examples of additional publishers who provided detailed guidelines are provided in Table 2. These publishers highlighted the value of making these materials easily accessible so that other researchers could use them, and welcomed supporting information that cannot be included in the print format, such as videos and large data sets. Other publishers only briefly mentioned supplementary materials and provided minimal guidance for authors. Policies ranged in size from one sentence to several pages in length.

Peer review of supplementary materials was not covered in much depth in many of these policies (see Table 2). Some indicated that supplementary materials would not be edited or revised and did not have to comply with the same guidelines as the article. Some journals included a disclaimer that the publisher was not responsible for the content or functionality of the supplementary materials and recommended that questions about them be directed to the author. For some publishers, the reviewers were asked to comment on whether all the supplementary materials were necessary for the article. In other policies, the quality and presentation of the supplementary materials were expected to be on the same level as the main article, and they were subjected to peer-review alongside the article. Only a few of the publishers in our study, such as the American Society of Plant Biologists, Company of Biologists, and AGU, clearly stated in their policy that all supplemental materials will be reviewed as part of the normal manuscript review process.

Discussions of metadata for supplementary materials also seemed to be lacking from many of the policies for the journals in our study (Table 2). Some publishers such as Institute of Physics Publishing and AGU required authors to submit a "readme file" with detailed descriptions of the supplementary materials and how to use the files. Others specified file naming conventions. BioMedCentral requires titles, descriptions, file names and file extensions for all the supplementary materials. Concise, descriptive captions were provided for the supplementary data for some journals, but many of the materials we observed had very limited metadata to help users understand their content, value, and relevance to the article.

Most policies included recommendations on file formats and file sizes for supplementary materials (Table 2). The limits on the total file sizes of supplementary materials allowed per article in our study ranged from 5 MB to 150 MB. Some publishers recommended a maximum file size of 10 MB due to the difficulties users might experience in loading or downloading larger files. Several publishers placed tight restrictions on the file formats required for supplementary materials, while others accepted a wide variety of formats. The publisher Springer encouraged authors to use file formats that would allow users to easily interact with and re-use the data.

Access issues were only occasionally discussed in the guidelines. More detailed policies provided helpful information about how users would be able to find these supplementary materials, such as through hyperlinks in the article, footnotes, and links from the tables of contents. Some publishers made the supplemental materials freely available via open-access data repositories, while others limited access to journal subscribers, and a few required additional fees for these materials. Publishers such as Wiley-Blackwell specified that the supplementary materials could also be made freely accessible on the author's web site or in an institutional repository and that in those cases the author would be responsible for ensuring that the URL for the supporting material remained valid for the lifetime of the articles. For journals published by the Geological Society of America, supplementary materials were assigned unique identifiers and stored on a separate web site without direct links back to the original article. Currently, the access points and links to and from supplementary materials vary widely. Librarians may be able to help facilitate access to these sometimes hard-to-find research materials.

Long-term archiving was also seldom mentioned directly in these policies. To help preserve these materials over the long term, several publishers recommended specific file formats that they could easily update as needed. Publishers such as AGU made a strong commitment to maintaining long-term access to supplementary materials and other data sets in their data policy (American Geophysical Union n.d.). Other publishers, such as Annual Reviews, noted that they would keep the supplemental materials in their web repository as long as practical; however, if forced to remove data in the future, they would remove older data or exceptionally large files first, and recommended that authors maintain copies of their supplemental materials.

Table 2. Comparison of Selected Features of Publisher's Policies on Supplementary Materials

| Publisher | Detailed Guidelines? | Peer-review? | Metadata? | Added Fees? | Recommended File Formats? | Size Limit/Article? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

American Geophysical Union |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

50 MB |

American Institute of Biological Sciences |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

10 minute limit on video & audio files |

American Meteorological Society |

No |

Unclear |

No |

$50/page |

Yes |

No |

American Phytopathological Society |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

$20/item |

Yes |

No |

American Society of Plant Biologists |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

10 MB |

Annual Reviews |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

BioMed Central |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

20 MB/file |

Cell Press |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Co-Action |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Company of Biologists |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

5 MB |

Copernicus/EGU |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

50 MB |

CSIRO |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Elsevier |

Yes |

Unclear |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

50 MB |

Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology |

Yes |

Unclear |

Yes |

$160/item |

Yes |

25 MB/file |

Geological Society of America |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

50 MB |

Inter-Research |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Institute of Physics |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

3 MB |

Nature Publishing Group |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

150 MB (30 MB/file) |

NRC Research Press |

No |

Unclear |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Oxford University Press |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Public Library of Science |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

10 MB |

|

Royal Society |

Yes |

Unclear |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

10 MB |

Springer |

Yes |

Unclear |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Taylor & Francis |

Yes |

In some cases |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

10 MB |

Wiley-Blackwell |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

10 MB |

Evolving Best Practices

Our results suggest the growing importance of supplementary materials to all who work with, use, produce, or otherwise interact with scholarly publishing. While a Wild West environment has reigned for the past decade, we are potentially moving towards a better understanding of the issues involved. For example, to help address long-term preservation, metadata, discoverability, citing, and other issues, the recent publication of Recommended Practices for Online Supplemental Journal Article Materials (NISO/NFAIS 2013) provides a wealth of information about business practices and technical issues related to supplementary materials.

Many of the best practice recommendations make an important distinction between two types of supplementary materials: "integral content", which is defined as material that is essential to the full understanding of the article, and "additional content" which might enhance a reader's understanding of the subject area, but is not considered essential for understanding the article. As technology changes, there is speculation that the integral content materials will become better integrated into the article, and this type of supplementary materials may disappear. For now, the best practice recommendations for integral content, such as detailed methods and primary data, include treating them at the same level as the rest of the article in terms of peer review, metadata, and long-term archiving. The guidelines for additional content, such as extended bibliographies, are more flexible and take into account the large diversity of formats that additional content may include.

While these recommended best practices were primarily written for publishers, they also address important roles for librarians, authors, editors, and peer reviewers in improving access to supplemental materials. Some examples of library roles include serving as a repository for research conducted at their institution to ensure long-term access to the supplemental materials and ensuring that supplemental materials are included with journal article interlibrary loan requests. Librarians who are becoming more involved in local scholarly communications issues at their institutions may play a role in advising, consulting, and educating local authors about supplementary materials and how to improve their use of them.

Conclusion

Supplementary materials present myriad opportunities for study. In looking at these 60 journals -- a subsection of the larger universe of actively published journal literature -- there is clearly a trend towards the rising use of these materials. This trend may very well extend to other journals throughout the environmental sciences, and other natural and applied sciences. However, huge gaps remain in our understanding of how and why researchers choose to include supplementary materials with their articles, or even, how often and in what ways these supplementary materials are being used. Variations appear to exist between subjects, types of journals, and even the methods employed by researchers. Journal policies vary widely in their treatment, from considering them as contributions to the scholarly record to treating them as simple vaults in which researchers can put anything they would like. Publishers face their own pressures -- such as the extra burden that monitoring these materials creates -- but the lack of a standard approach makes understanding the use and purpose of these materials difficult.

Library users currently face a variety of challenges in getting access to supplemental materials. They are not currently included in most indexing and abstracting services, so users may not even be aware that they are available to enhance or support an article. Supplemental materials can be overlooked or difficult to request through the interlibrary loan process. Limited metadata and missing links can hinder the use of these materials. The new recommended practices for supplemental materials have the potential to help users discover and access these materials more easily. Publishers are encouraged to provide clear, consistent links to these materials from the journal's table of contents. Another key best practice that will help users is to provide persistent identifiers, preferably DOIs to ensure long-term access. An increased awareness of the value of these supplemental materials and advocacy on the part of librarians to improve access and archiving of these materials is needed.

At the University of Idaho, this investigation has greatly improved our understanding of the availability and dynamics of supplementary materials. As subject librarians responsible for instruction to our respective departments, we have begun to introduce the best practices around the production of supplementary materials into discussion with faculty and graduate students. The publisher policies have been introduced to our scholarly communications program -- for inclusion in open access presentations and discussions. Lastly, as we continue to pursue library services surrounding research data management -- a better understanding of the role that supplementary materials play in scholarly communications is helping to clarify the boundaries between data sharing via journals and data sharing via repositories. As supplementary materials play an increasing role in scholarly work, understanding these materials will enable us to be more supportive of our university community.

References

American Geophysical Union. n.d. Policy on referencing data in and archiving data for AGU publications. [Internet]. [Cited 2013 August]. Available from: http://publications.agu.org/author-resource-center/publication-policies/data-policy/

Anderson, N.R., Tarczy-Hornoch, P., and Bumgarner, R.E. 2006. On the persistence of supplementary resources in biomedical publications. BMC Bioinformatics 7:260-7.

Beebe, L. 2010. Supplemental materials for journal articles: NISO/NFAIS Joint Working Group. Information Standards Quarterly 22(3):33-37.

Borowski, C. 2011. Enough is enough. Journal of Experimental Medicine 208(7): 1337. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20111061

Carpenter, T. 2009. Journal article supplementary materials: A Pandora's box of issues needing best practices. Against the Grain 21(6):84-85.

Carpenter, T. 2010a. Outside the core: working towards an industry recommended practice for supplemental journal materials. Serials 23(2):155-158.

Carpenter, T. 2010b. Taming the world of data: pressures to improve data management in scholarly communications. Against the Grain 22(6):84-85.

Davis, P.M. 2008. Eigenfactor: Does the principle of repeated improvement result in better estimates than raw citation counts? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60:3-8.

Hanson, B., Sugden, A., and Alberts, B. 2011. Making data maximally available. Science 331:649.

Laue, A. 2010. Hosting supplementary material: technical challenges and suggested best practices. Information Standards Quarterly 22(3):10-15.

Lorbeer, E.R. and Klusendorf, H. 2010. Open and accessible supplemental data: how librarians can solve the supplemental data arms race. Against the Grain 22(6):42-43.

Marcus, E. 2009. Taming supplemental material. Cell 139(1):11-11.

Maunsell, J. 2010. Announcement regarding supplemental material. The Journal of Neuroscience 30(32):10599-10600.

Moed, H. 2005. Citation analysis in research evaluation. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

NISO/NFAIS. 2013. Recommended practices for online supplemental journal article materials. National Information Standards Organization and the National Federation of Advanced Information Services. NISO RP-15-2013. Available from: http://www.niso.org/publications/rp/rp-15-2013

Rosenthal, D. and Reich, V.A. 2010. Archiving supplemental materials. Information Standards Quarterly 22(3).

Schaffer, T. and Jackson, K.M. 2004. The use of online supplementary material in high-impact scientific journals. Science & Technology Libraries 25(1/2):73-85.

Schwarzman, S. 2009. Supporting material. [Internet]. [Cited 2012 September]. American Geophysical Union. Available from: http://www.agu.org/dtd/Presentations/sup-mat/

Smit, E. 2011. Abelard and Heloise: why data and publications belong together. D-Lib Magazine [Internet]. [Accessed February 11, 2014]. 17(1/2). Available from: http://www.dlib.org/dlib/january11/smit/01smit.html

Williams, S.C. 2013. Data sharing interviews with crop science faculty: Why they share data and how the library can help. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship 72. Available from: http://www.istl.org/13-spring/refereed2.html

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Journal Rankings. Journal rankings used for journal selection with final ranking score. (Excel file)

Appendix 2. Percentage of Articles with Supplementary Materials. Numerical data supporting Figure 2. (Excel file)

Appendix 3. Links to Policies for Supplementary Materials. Provides links to publisher guidelines and policies described in Table 2. (Excel file)

| Previous | Contents | Next |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.