Using Participatory and Service Design to Identify Emerging Needs and Perceptions of Library Services among Science and Engineering Researchers Based at a Satellite Campus

Andrew Johnson

Research Data Librarian

University Libraries

University of Colorado Boulder

Boulder, Colorado

andrew.m.johnson@colorado.edu

Rebecca Kuglitsch

Head, Gemmill Library of Engineering, Math & Physics

University Libraries

University of Colorado Boulder

Boulder, Colorado

rebecca.kuglitsch@colorado.edu

Megan Bresnahan

Team Lead for Sciences & Social Sciences

Tisch Library

Tufts University

Medford, Massachusetts

megan.bresnahan@tufts.edu

Abstract

This study used participatory and service design methods to identify emerging research needs and existing perceptions of library services among science and engineering faculty, post-graduate, and graduate student researchers based at a satellite campus at the University of Colorado Boulder. These methods, and the results of the study, allowed us to uncover barriers in the research processes of a user population without a dedicated physical library. This article describes our participatory and service design approach, the results of the exercises and interviews we conducted with researchers, and our current or planned implementations of services to address researcher needs based on what we learned from the study.

Introduction

Providing meaningful, relevant services to faculty and graduate students in the sciences and engineering is a challenge for libraries. For many of our users, the library is seen as a purchaser of expensive resources rather than a gateway to research, archival preserver of knowledge, or partner in the intellectual life of the university (Guthrie & Housewright 2010). As the findings of the 2012 Ithaka S+R survey suggest, developing relevant services for scientists, and making it clear that they exist, is increasingly urgent if libraries expect to continue to serve that population (Housewright et al. 2013). Without "identify[ing] and implement[ing] valuable services that rely on geographic proximity," libraries will be hard pressed to remain relevant to this population in particular (Guthrie & Housewright 2010: 102).

But, then, how can librarians identify those valuable services and most effectively target this population? We suggest that methods of participatory design and service design will allow librarians to efficiently identify and implement locally relevant services, particularly for researchers in the sciences and applied sciences. This method gives us access to information we might not otherwise be able to obtain: it allows us to understand the holistic landscape of researcher needs, to rapidly learn of changes in researcher practices, and to identify researcher priorities for library service. Participatory design can be particularly useful in gathering information from heterogeneous, difficult to reach populations (Brown-Sica et al. 2010). Freeman and Pukkila (2012) applied this method to studying faculty but focused only on "...those persons that we thought would enjoy working with us on this type of project; usually they were people who had already worked with us on library and/or ITS matters." The present study focuses on users who do not use library services at all or who, for example, only use the library to access electronic journal articles, our goal being to identify what services a group not already invested in the library might need. The target population for this investigation, faculty and graduate science researchers, is in many ways inherently difficult to reach. This challenge is largely due to their heavy reliance on online resources, busy schedules, and limited understanding of the potential value of the library as a partner in the research process, but geography also plays a role. Our study focused on extending services to researchers on a satellite campus without any library service points that is located approximately one mile from the main campus.

We used participatory and service design methods to identify gaps in the research process that we might not otherwise recognize and to find opportunities to promote or develop new library services for science and engineering researchers. Foster (2012) defines participatory design as "an approach to building spaces, services, and tools where the people who will use those things participate centrally in coming up with concepts and then designing the actual products." Similarly, Marquez and Downey (2015) describe service design as "a holistic, co-creative, and user-centered approach to understanding customer behavior for the creation or refining of services." These methods helped us reach library non-users, as well as users who might not identify themselves as such. For example, researchers who make heavy use of online resources may not see themselves as 'library users.' The techniques we employed in this study elicited information about faculty and graduate student research processes in a way that allowed us to identify gaps the library could fill rather than placing the onus on the researcher to identify how the library could help them.

Background

At our institution, a number of research laboratories, offices, and institutes in the sciences have been relocated to an area of campus (East Campus) that currently has no physical library presence. A significant portion of course instruction in the sciences is also expected to move to East Campus in the coming years. Departments and institutes currently housed on East Campus include, the BioFrontiers Institute, the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR), Chemical and Biological Engineering, and Chemistry and Biochemistry. The library is interested in adapting services to better accommodate these new educational and research endeavors.

Literature Review

There is a significant body of literature on faculty and graduate student perceptions of library roles, as well as faculty and graduate student needs (which are not always synonymous with perceived roles). Many of these studies rely on traditional research methods: surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Our study draws from the also substantial literature on participatory design and the nascent literature on service design to propose a method that allows librarians to understand perceptions and needs of faculty and graduate student researchers.

Faculty perceptions of library roles have been well investigated. The Ithaka S+R reports provide a longitudinal view of some areas of faculty perception. An analysis of the 2009 Ithaka S+R report found faculty had a very limited perception of library roles, viewing the library primarily as fulfilling the role of buyer of content, rather than an archiver or starting point for research (Guthrie & Housewright 2010). In the sciences, this content-purchaser role was particularly pervasive and coupled with a lack of awareness of other possible roles; for example, less than half of the faculty surveyed who identified themselves as belonging to the sciences rated the library's role as gateway to research as very important, and, while only 20% rated the library's role as much less important, that number had more than doubled since 2006 when the survey had last been conducted (Guthrie & Housewright 2010: 88, 102). Three years later, similar themes emerged. The library's role as buyer continued to be consistently rated as very important, and, again, still fewer scientists rated the gateway or archival roles of libraries as important or very important (Housewright et al. 2013). Other studies have confirmed these limited perceptions. A study at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, focusing on faculty attitudes related to research, found that many faculty rate the library as important or very important to their productivity, but they rarely perceive services other than buying resources or providing access to them as important (Brown & Tucker 2013). A qualitative study of basic science researchers reported that researchers generally had positive perceptions of the library but rarely took advantage of its offerings, preferring to simply take care of tasks within their lab groups or by reaching out to colleagues (Haines et al. 2010). A survey of engineering faculty, in particular, suggests that access to journals, preferentially electronic, is perceived as a particularly key function of the library, with little importance placed on physical library spaces (Engel et al. 2011).

Like faculty, graduate students are not necessarily dissatisfied with the library services they receive, but they are not fully aware of the breadth of potential services. A study at the University of Notre Dame found that graduate students had limited contacts with librarians and outreach services, but the majority nonetheless rated the library as useful or very useful (Kayongo & Helm 2010). Jankowska, Hertel and Young (2006) used LibQUAL+ data to access graduate student perceptions of the library and found a similar lack of awareness of the services offered by the library. Gibbs, Boettcher, Hollingsworth, and Slania (2012) surveyed graduate students across the disciplines, and found that graduate students tended to have limited ideas of what libraries offered and little sense of the breadth of possible services. In addition, despite rarely asking for help, graduate students had trouble finding and accessing journal articles, wanted specific resources that were not available, and had difficulty understanding library web sites (Gibbs et al. 2012). Overall, students conceived of the library as mainly for providing access to information and resources like software or technology, as well as a productive, comfortable space for literature research; most did not know that there was a liaison librarian assigned to their program (Gibbs et al. 2012). These limited perceptions of library roles do not necessarily reflect a lack of need as much as a lack of awareness of need.

While researchers have a limited conception of library services, many libraries have expanded their service offerings to meet the changing needs of science researchers who are operating in a technologically complex and voluminous research arena. For example, studies on the information seeking behavior of academic researchers have revealed a need for access to online materials and online management tools (Hemminger et al. 2007; Niu et al. 2010). Antonijević and Cahoy (2014) found that that even in a digital environment, faculty in the sciences feel a strong need for personal libraries of resources managed with online tools, with varying degrees of expectation for workflow interconnectedness and integration. Data management has also been identified as a need. Carlson, Fosmire, Miller, and Nelson (2011) interviewed faculty about their data management needs and concluded that faculty need graduate students to have more training in data management, as most training is ad hoc and inconsistent. Faculty also identified a need for data management services on their own behalf (Beagrie et al. 2009).

Studies of graduate student needs have emphasized more interest in personal interactions and research assistance at the library. A user needs assessment at the University of Iowa indicated that graduate and professional students would like more human contact and assistance using the library, including instruction (Barton et al. 2002). A later investigation into the instructional needs of STEM students found that students desired instruction in finding information, managing information, and staying current, delivered either in person or, preferentially, online. Ideally, students wanted subject-specific instruction, as well as general instruction (Hoffman et al. 2008). This need for subject expertise was echoed by the students surveyed by Gibbs, Boettcher, Hollingsworth, and Slania (2012) who identified doubts about librarians' subject expertise as one factor in avoiding in-person research assistance. Rempel, Hussong-Christian, and Mellinger (2011) used focus groups to examine graduate student needs and identified large scale needs for campus-wide support of graduate students as developing teachers and researchers; while the library cannot unilaterally solve these needs, it can provide leadership in beginning to meet them. This more personally focused yet holistic assessment revealed deeper and more complex needs than a survey might have, such as a database of ongoing campus research projects to facilitate interdisciplinary and cross-campus connections (Rempel et al. 2011: 484).

While it is clear from the literature that faculty and graduate students have needs that the library can satisfy, it is equally clear that they may not perceive libraries as possible solutions. We sought a method that could help us identify meaningful information for our practice. Robbins, Engel, and Kulp (2011) reviewed survey data on engineering researcher needs, concluding that information on faculty needs and behavior gathered via survey often left the authors without actionable, meaningful information. Participatory design offers a way for librarians to move beyond descriptive surveys to actionable research. If users are specialists in their work habits, what they need, what they like, what they wish they could work with, participatory design provides a way for them to contribute that specialist knowledge to library designers (Foster 2012). Participatory design is particularly useful in the mutually jargon-ridden case of librarians and researchers, as it offers a way to translate the different languages stakeholders speak (Foster 2012). Moreover, as Somerville (2009) notes, participatory design inherently involves clarifying dialogue, which can provide a better understanding of user needs and perspectives.

The literature around participatory design in libraries is substantial, but largely focused on space design, though there is a growing integration of the method into service design as well. Perhaps the founding document of participatory design studies in libraries is Foster and Gibbons' Studying Students (2007), updated in 2013 in Studying Students: A Second Look (2013). These books recounted how numerous participatory methods were applied to understand how undergraduate students perform research. Many are space related, as are the case studies in the Council on Library and Information Resources report on participatory design (Council on Library and Information Resources 2012). Other space-related applications include the extensive work in the Auraria Libraries (Brown-Sica et al. 2010; Somerville & Brown-Sica 2011). In their study of participatory design applied to developing the learning commons, Brown-Sica, Sobel, and Rogers (2010) highlighted the utility of participatory design in particular for circumventing the barriers of preconceptions and past practices in order to identify new needs. Foster, Dimmock and Bersani (2008) used a participatory design method to redesign the University of Rochester's River Campus Libraries web presence. This project used a very visual process to ask students to design their ideal library web site. The visualization enabled researchers to efficiently collect rich data on web site features needed and desired by users (Foster et al. 2008). Freeman and Pukkila (2012) studied faculty research practices, interviewing a small group of faculty about their research and teaching methods in order to identify support opportunities; they conclude that faculty research is highly individualized, so library services must be as well. More recently, Marquez and Downey (2015) applied participatory design methods to service design. Their co-creative process allows a focus on demand and need from users, while maintaining a holistic awareness of how library services interact to provide a satisfying user experience (Marquez & Downey 2015). Along with elements of participatory design, our study combines this service design approach with a focus on faculty and graduate students outside of the physical library.

Methods

This study used participatory design and service design methods in order to explore science and engineering researcher needs and behaviors in a satellite campus setting for fields that make relatively light use of the university's physical library resources. To reach our population of interest, we recruited faculty and graduate students from research centers on the university's East Campus via e-mail for in-person research sessions. In order to conduct interviews and participatory design activities in a comfortable work setting, participants were encouraged to meet with the research team in their own space (their lab or office), but they could choose to meet with the research team on the main campus, if preferred.

The in-person interviews and activities with participants took approximately 30-45 minutes. The sessions consisted of:

- An interview, which established the tone of the session and provided an opportunity to ask about past library experiences and known desired services;

- A research process drawing activity, which allowed us to understand the research process and identify opportunities for library services;

- And, a 'magic button' activity, where researchers were asked to draw a button they could use to solve any problem related to their research.

The interview portion opened the session and provided an opportunity to ask about current experiences and desired services. Participants were asked to describe their current research projects and their experiences using scholarly resources in the context of that project. This served both as an icebreaker and as a way to understand the researcher's vocabulary, how they talk about their research, and at times even, what excites them about their work. We next asked about their most recent library experience, including a short description of it, the level of quality of the experience, and how it might be improved. Finally, we asked participants to describe ideal new library services.

The visual activities followed the interview questions. First, we asked participants to draw a visual representation of their research process, beginning with their initial research idea and following through to post-publication. Participants were prompted to think about their information gathering process, research strategies, research dissemination, and challenges throughout the process. After completing this drawing, they were asked to mark where the library currently has a role in their research. Next, they were asked to mark where they could imagine the library providing support in their research.

We concluded with a 'magic button' exercise during which participants were asked to turn the paper used for the visualization exercise over and draw a square containing a circle. They were then told that this was a button that would magically eliminate a problem or frustration of the research process, and participants were asked to describe what they would use the magic button to change. This activity, in particular, was designed to elicit responses that could help us to identify services we could offer that researchers would not have imagined themselves.

After the interviews and activities were completed with all participants, the research team met to analyze the collected materials. The team reviewed all materials together, established shared definitions, and identified common themes from the interview responses, research process drawings, and magic button exercise answers from both participant groups (graduate students and faculty/post-graduate researchers). These themes were then used to identify areas of need and potential service opportunities that the library could support with regard to the target population of the study.

Results

Six graduate students and six faculty and post-graduate researchers, whose offices were located on East Campus, participated in this study. Graduate students came from the departments of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Chemistry and Biochemistry (two), Ecology and Evolutionary Biology/INSTAAR, Environmental Studies/INSTAAR, and Geological Sciences/INSTAAR. Faculty and post-graduate researchers came from the departments of Chemistry and Biochemistry (three), Geological Sciences/INSTAAR, Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, and the National Ecological Observatory Network/INSTAAR.

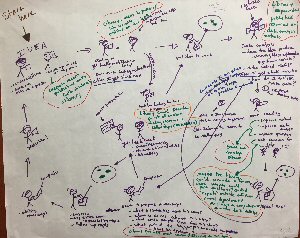

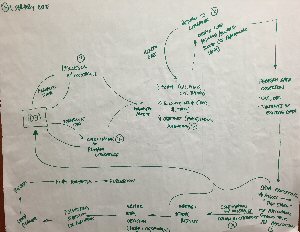

Visualizing Research Processes

We asked participants to create visual representations of their research processes. See Figures 1 and 2 for examples of these drawings. Visually, nearly every representation consisted of a cyclical process that typically included smaller cycles within it. This was consistent across both the graduate student and faculty/post-graduate groups. Unsurprisingly, various degrees of collaboration with advisors, students, lab-mates, and collaborators in other departments and at other institutions were present in all drawings. Nearly all drawings began with an idea generation stage. Other stages varied by participant, but most also included (in some combination and order) literature reviews, experiments, data analysis, idea and/or method refinement, writing, and sharing results both informally and formally with colleagues.

Figure 1. Example of graduate student visual activity (Click to enlarge image)

Figure 2. Example of faculty/post-graduate visual activity (Click to enlarge image)

Identifying Current Library Roles

During the interview portion, we asked participants about their most recent experience using the library or library resources. All faculty and post-graduate researchers mentioned using the library catalog, databases, or interlibrary loan to access electronic journal articles. Only one participant from this group mentioned using the physical library, and that individual reported a negative experience trying and failing to find a book. Several graduate students described using interlibrary loan, and one mentioned using library resources to create "personal libraries" of both physical and electronic books and articles. In addition, several graduate students mentioned frustrating experiences with electronic access to journal articles. This differed from faculty and post-graduate experiences with electronic access, which were mostly positive.

We also asked participants to identify the specific places in which the library plays a significant role on the visual representations they created of their research processes. The number of places varied across participants; however, in every case the role of the library was as provider of content resources. Again, the type of content provided and the purpose for which it was used varied across participants as well as within individual drawings. For example, participants consulted library resources for their literature reviews for journal articles and grant proposals, to assess whether an idea for a research project was novel, to identify methods and protocols for experiments, to refine research questions, and to troubleshoot problems with experiments. In nearly all cases, library resources were accessed electronically.

Imagining New Library Roles

During the interview, we asked participants to imagine what new library services on East Campus might be useful to them. Nearly all faculty and post-graduate participants gave some version of "easier electronic access to journal articles" as the sole library service they could imagine they would need; however, one participant did note that a dedicated librarian and space for browsing physical collections would be useful. Graduate student responses were more varied. Graduate student participants described the following library services they would like to see on East Campus:

- Library spaces for convenient access to workshops, group work, browsing collections, and promotion of library services/resources;

- Workshops/tutorials/seminars on skills/tools useful for research;

- Easier electronic access to journal articles;

- Dedicated e-mail, phone, and in-person support from librarians;

In contrast to the faculty responses, graduate students emphasized new library roles that included physical spaces, dedicated support, and learning opportunities in addition to access to electronic resources.

Identifying Barriers in Research Processes

As described earlier, we asked each participant to draw a "magic button" that would eliminate their biggest problem or barrier in their research process, which they stated after drawing the button. Graduate student participants gave the following responses as the most significant barriers to their research:

- Knowing what experiments have already been done and which have failed;

- Avoiding contamination in samples;

- Understanding how to analyze data;

- Keeping up with the literature;

- Spending time monitoring a very sensitive instrument while it runs;

- Finding a research question and knowing which methods to use to answer it.

Faculty and post-graduate researchers stated that the following were their biggest frustrations in their research processes:

- Predicting experimental results based on inadequate descriptions in the literature;

- Having to use obsolete software and proprietary instruments;

- Communicating with lab members;

- Filtering out time-intensive requests for "lab services" from requests for actual collaboration;

- Acquiring grant funding;

- Accessing information behind paywalls.

Increasing research efficiency and productivity was a common theme across many of the barriers from both groups. Given the demands placed on both graduate students and faculty, it is understandable that barriers would involve time-intensive activities that are perhaps deemed less essential than other parts of the research process. Several barriers across the two groups involved issues with the current system of scholarly communication, including the lack of negative results in the literature, the paywalls that prevent access to research, the inability to replicate experiments from inadequate descriptions in journal articles, and the difficulty in keeping up with the volume of published literature.

Discussion

The visual representation exercise provided a quick way to get an overview of participants' research processes. These drawings helped us to identify common characteristics, like iterative cycles and collaboration, that emerged from nearly all drawings as well as places where the library commonly played a role in researchers' work. Perhaps not surprisingly given the lack of a physical library presence on East Campus, providing electronic access to resources was the primary role that the library played across all participants' responses. That said, the drawings and interviews allowed us to see when and how library resources were being used during the course of participants' research workflows. More surprisingly, even when given an open-ended opportunity to reimagine library services and support for research, many participants (including all faculty and post-graduate participants) focused exclusively on electronic access to the research literature. Graduate students envisioned a wider variety of potential roles new library services could provide on East Campus, including community spaces, specialized expertise, and instruction covering a range of skills and tools.

While participants' visions for library services were somewhat narrow, the wide range of barriers and challenges that they identified in their research processes during the "magic button" exercise could provide potential opportunities for us to provide research support. In fact, we already offer support in some of these areas; however, participants were unaware of the current services and also did not think that the library would be the place to turn for such support. For example, several participants mentioned needing help with problems related to data management and open access publishing (e.g., "having to use obsolete software and proprietary instruments" and "accessing information behind paywalls"), but they stated that they would not have thought to look to the library for this type of help. In addition, the library clearly provides support for needs like "identifying a research question" and "keeping up with the literature", and while participants did not explicitly state that they would not turn to the library for help with these problems, the fact that these barriers remain suggests that either participants are unaware of this library support or are unwilling to use it for some reason. All of these responses indicate a need for better promotion and/or reexamination of existing library services and point to areas that could benefit from additional library support.

In response to the feedback we received from the graduate student participants, we were able to develop and implement a workshop series on research skills and tools that we delivered on East Campus using space in one of the institutes housed there. The topics of these workshops were informed by the needs that we identified in the study, including data management and open access. Similarly, we held a Software Carpentry workshop for graduate students in STEM disciplines at one of the main campus libraries that serves this population. That workshop was also informed by graduate student desires expressed in the interviews for workshops on software and data analysis skills. In addition, we were able to use the results of this study to advocate for a library consultation space in a new building being built on East Campus in order to provide the personalized service that graduate students indicated they would like to have near their work and study spaces. While not yet implemented, we are planning a series of workshops on more advanced data analysis methods and tools to help address the barrier related to knowing how to analyze data that graduate students expressed.

Many of the barriers that faculty and post-graduate researchers described related to larger issues with the way research is conducted and communicated. Issues like articles behind paywalls, decreased grant funding, proprietary formats, and improperly documented experiments all reach far beyond this campus, yet we have been working to enact change in these areas through advocacy, outreach, and consultation. While we may not be able to offer services to directly address these barriers, the results reinforce the need for existing efforts around open access and research data management to continue to grow here and at other institutions in order for the culture that is creating these difficulties to change. See Tables 1 and 2 for a full list of barriers identified and existing or planned services to address these needs.

Table 1. Barriers graduate students identified that library services could address

| Barriers or needs identified during study | Services existing at time of study | Services planned or implemented since time of study |

|---|---|---|

Knowing what experiments have already been done and which have failed |

|

|

Understanding how to analyze data |

|

|

Keeping up with the literature |

|

|

Finding a research question and knowing which methods to use to answer it |

|

|

Library spaces for convenient access to workshops, group work, browsing collections, and promotion of library services/resources |

|

|

Dedicated email, phone, and in-person, East Campus support from librarians |

|

|

Workshops/tutorials/seminars on skills/tools useful for research |

|

|

Easier electronic access to journal articles |

|

|

Table 2. Barriers faculty and post-graduate researchers identified that library services could address

| Barriers or needs identified during study | Services existing at time of study | Next steps |

|---|---|---|

Communicating with lab members |

|

|

Acquiring grant funding |

|

|

Accessing information behind paywalls |

|

|

Conclusions and Future Directions

The participatory design and service design methods used in this study allowed us to reach and better understand the research needs of a science and engineering population on our campus that is currently without a physical library presence. The results from the exercises and interview questions provided a holistic picture of the research practices of these users, including areas in which the library currently plays a role as well as potential services we could provide based on suggestions from participants and the barriers to their research that they identified. Indeed, we were able to implement some of these services immediately following the conclusion of the study. Several barriers stemmed from larger and more complex issues with the research process itself while others simply fell outside of the scope of probable library solutions (e.g., "avoiding contamination in samples").

There are several possible future directions for this work. For example, we identified gaps in service as well as a gap between what the libraries are perceived to offer and what they actually offer, but we did not identify a way to change the perceptions. In Freeman and Pukkila's (2012) study, they partnered with academic technologists with productive results. A future approach to further research might involve partnering with key individuals at the research centers on East Campus, including outreach staff, administrative assistants, lab managers, and IT personnel. There is an active "communicators group" on East Campus, including outreach officers, program administrators, and others form the various research centers. In our study, we leveraged this network to publicize the study rather than for mutual aid; however, both groups have overlapping interests in supporting open access publishing efforts, disseminating local resources, supporting data management, and demonstrating impact, among others. Reaching out to other partners at the university could also help to address barriers that we have been unable to tackle so far, including tools to enhance and streamline collaboration among faculty. Another group at our institution is developing a VIVO profiles system for campus faculty that could help with these issues, and we can reach out to that group to ensure that the faculty needs identified in this study are addressed.

Finally, both participatory design and service design methods emphasize iterative processes, so we will need to continue to engage with our target population to ensure that the services we have already developed are actually meeting their needs. The same can be said for any additional services or spaces we design as the East Campus landscape continues to evolve with new buildings being built and course instruction soon taking place there. With the wider research environment also changing, it will be of utmost importance to continue to use methods like these to better understand our users and their needs.

References

Antonijević, S. and Cahoy, E.S. 2014. Personal library curation: An ethnographic study of scholars' information practices. portal: Libraries and the Academy 14(2):287-306.

Barton, H., Cheng, J., Clougherty, L., Forys, J., Lyles, T., Persson, D.M., Walters, C., and Washington-Hoagland, C. 2002. Identifying the resource and service needs of graduate and professional students. portal: Libraries and the Academy 2(1):125-143.

Beagrie, N., Beagrie, R., and Rowlands, I. 2009. Research data preservation and access: The views of researchers. Ariadne [Internet]. [Cited 2015 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue60/beagrie-et-al

Brown, J.M. and Tucker, C. 2013. Expanding library support of faculty research: Exploring readiness. portal: Libraries and the Academy 13(3):257-271.

Brown-Sica, M., Sobel, K., and Rogers, E. 2010. Participatory action research in learning commons design planning. New Library World 111(7/8):302-319.

Carlson, J., Fosmire, M., Miller, C.C., and Nelson, M.S. 2011. Determining data information literacy needs: A study of students and research faculty. portal: Libraries and the Academy 11(2):629-657.

Council on Library and Information Resources. 2012. Participatory design in academic libraries: methods, findings and implementations. Washington DC: Council on Library and Information Resources Report No. 155. [Internet] [Cited 2014 Jul 1]. Available from: http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub155

Engel, D., Robbins, S., and Kulp, C. 2011. The information-seeking habits of engineering faculty. College & Research Libraries 72(6):548-567.

Foster, N.F. 2012. Introduction. In: Participatory Design in Academic Libraries: Methods, Findings and Implementations. Washington DC: Council on Library and Information Resources. p. 1-4. [Internet]. [Cited 2014 Jul 1]. Available from: http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub155

Foster, N.F., editor. 2013. Studying Students: A Second Look. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Foster, N.F., Dimmock N., and Bersani, A. 2008. Participatory design of websites with web design workshops. The Code4Lib Journal [Internet]. [Cited 2014 Jul 3]. Available from: http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/53

Foster, N.F. and Gibbons, S., editors. 2007. Studying Students: The Undergraduate Research Project at the University of Rochester. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Freeman, E. and Pukkila, M.R. 2012. Faculty in the mist: Ethnographic study of faculty research practices. In: Participatory Design in Academic Libraries: Methods, Findings and Implementations. Washington DC: Council on Library and Information Resources. p. 4-10. [Internet]. [Cited 2014 Jul 1]. Available from: http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub155

Gibbs, D., Boettcher, J., Hollingsworth, J., and Slania, H. 2012. Assessing the research needs of graduate students at georgetown university. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 38(5):268-276.

Guthrie, K. and Housewright, R. 2010. Repackaging the library: What do faculty think? Journal of Library Administration 51(1):77-104.

Haines, L.L., Light, J., O'Malley, D., and Delwiche, F.A. 2010. Information-seeking behavior of basic science researchers: Implications for library services. Journal of the Medical Library Association 98(1):73-81.

Hemminger, B.M., Lu, D., Vaughan, K.T.L., and Adams, S.J. 2007. Information seeking behavior of academic scientists. Journal of the American Society for Information and Technology. 58(14):2205-2225.

Hoffman, K., Antwi-Nsiah, F., Feng, V., Stanley, M. 2008. Library research skills: A needs assessment for graduate student workshops. Issues in Science & Technology Librarianship. DOI: 10.5062/F48P5XFC

Housewright, R., Schonfeld, R. and Wulfson, K. 2013. Ithaka S+R US Faculty Survey 2012. [Internet]. [Cited 2014 Jul 3]. Available from: http://www.sr.ithaka.org/sites/default/files/reports/Ithaka_SR_US_Faculty_Survey_2012_FINAL.pdf

Jankowska, M.A., Hertel, K., and Young, N.J. 2006. Improving library service quality to graduate students: Libqual+[TM] survey results in a practical setting. portal: Libraries and the Academy 6(1):59-76.

Kayongo, J. and Helm, C. 2010. Graduate students and the library: A survey of research practices and library use at the University of Notre Dame. Reference & User Services Quarterly 49(4):341-349.

Marquez, J. and Downey, A. 2015. Service design: An introduction to a holistic assessment methodology of library services. Weave: Journal of Library User Experience 1(2). DOI: 10.3998/weave.12535642.0001.201

Niu, X., Hemminger, B.M., Lown, C., Adams, S., Brown, C., Level, A., McLure, M., Powers, A., Tennant, M.R., and Cataldo, T. 2010. National study of information seeking behavior of academic researchers in the United States. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 61(5):869-890.

Rempel, H.G., Hussong-Christian, U., and Mellinger, M. 2011. Graduate student space and service needs: A recommendation for a cross-campus solution. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 37(6):480-487.

Robbins, S., Engel, D., and Kulp, C. 2011. How unique are our users? Comparing responses regarding the information-seeking habits of engineering faculty. College & Research Libraries 72(6):515-532.

Somerville, M.M. 2009. Working together: Collaborative Information Practices for Organizational Learning. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Somerville, M.M. and Brown-Sica, M. 2011. Library space planning: A participatory action research approach. The Electronic Library 29(5):669-681.

| Previous | Contents | Next |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.