| URLs in this document have been updated. Links enclosed in {curly brackets} have been changed. If a replacement link was located, the new URL was added and the link is active; if a new site could not be identified, the broken link was removed. |

The Prevalence and Quality of Source Attribution in Middle and High School Science Papers

Michelle Vieyra

Associate Professor of Biology

michellev@usca.edu

Kari Weaver

Associate Professor of Library Science and Library Instruction Coordinator

kariw@usca.edu

University of South Carolina Aiken

Aiken, South Carolina

Abstract

Plagiarism is a commonly cited problem in higher education, especially in scientific writing and assignments for science courses. Students may not intentionally plagiarize, but may instead be confused about what proper source attribution entails. Much of this confusion likely stems from high school, either from lack of or inconsistent instruction across classes. To determine the extent of plagiarism issues in middle and high school student science papers, the authors surveyed student research reports to evaluate their use of in-text and reference page citations. While most of the students had a reference page, fewer than 35% of high school students properly used in-text citations. Furthermore, 12th grade students did not perform any better than 9th grade students in providing proper citations. A survey of college science faculty showed that they do not feel that students are receiving adequate training in source citation in high school. While proper source citation, including the use of in-text citations, is clearly indicated in state education standards, students may not be receiving consistent instruction for a variety of reasons. At a minimum, teachers and officials who supervise student research projects should ensure that students give proper attribution to their sources. This will avoid the development of bad habits that may be troublesome in college.

Introduction and Hypotheses

Any discussion of research writing in the sciences will inevitably lead participants to the topic of plagiarism. Plagiarism has been cited as the most common form of academic misconduct at universities (Breen & Maassen 2005; McCabe 2005; Selwyn 2008) and it is particularly common in STEM classes (Simon et al. 2004; Sheard, Dick, Markham, McDonald & Walsh 2002; Yeo 2007). Most plagiarism studies rely on survey methods asking students and/or faculty to recognize instances of plagiarism in examples. Few studies have attempted to assess the degree of plagiarism actually occurring in student papers, especially at the important high school and middle school levels that feed into higher education. Given that confusion regarding how and when to cite sources likely begins in the pre-college years, this investigation contributes a new perspective to the body of literature by looking at source citation in student research reports at regional science fairs and state science conferences.

Plagiarism is a recognized problem at high school science fairs. According to the hosts of the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair, (Society for Science & the Public 2012b) plagiarism is one of the most common reasons for disqualification from the international fair. Regional science fair projects were selected for this investigation because they are presented at the school level and evaluated by teachers and judges before being presented at a regional science fair (Society for Science & the Public 2008; Savannah River Site 2012) providing ample opportunity for remediation. In addition, all of the projects at the regional science fairs sampled won awards at the school level (Society for Science & the Public 2008). How much instruction or mentoring the students received in the writing of their research reports was not known, but, regardless of the level of instruction, students were likely to infer that their citation strategies were adequate given that they won awards for their projects.

When students enter college with an inadequate understanding of proper source citation they often struggle to meet the expectations of collegiate level research. To support the assertion that proper source attribution is considered important in the college science classroom and to further inform high school science teachers about what college professors expect from entering freshmen, science faculty at the universities hosting the science fairs were surveyed regarding what they think actually is and what should be taught in high school about source use and attribution.

Based on the prevalence of plagiarism observed in the college classroom (Whitley 1998; Breen & Maasen 2005; McCabe 2005) and high school level (Dant 1986; McCabe and Katz 2009; Sisti 2007), the authors expected to find citation issues in a large percentage of the middle and high school research reports examined. The authors also expected most of the papers to have reference pages but fewer to have adequate citations within the text. Finally, there was hope the findings would reflect improvement in appropriate citation usage from sixth to twelfth grade. It was expected that college science faculty would expect at least a moderate amount of high school instruction regarding source use and citation and would perceive the importance of the instruction to be higher than the perceived amount of instruction given.

Literature Review

Librarians and classroom teachers have long been concerned with instructing students in the ethical use of information and attribution of source material. These concerns are featured prominently in both the American Association of School Librarians and Association for College and Research Libraries Standards and Framework Documents (AASL 2007; ACRL 2015). While an emphasis on proper documentation is shared widely across grade levels in the United States, it has also been found that most college students only completed one research-based assignment in high school, most frequently in their English class, and struggled to bring a variety of research skills to other disciplines in higher education settings (Head 2013).

Researched writing is a critical component of successfully engaging in a variety of academic disciplines, and it is particularly important in science (Yore et al. 2002; Yore et al. 2004). Writing has also been recognized as instrumental to learning science and increasing scientific literacy (Glynn & Muth 2006). Documentation, synthesis, and appropriate citation are integral to the writing process in the sciences, where source material must be accurately presented to allow for future replication of experimental design (Harwood 2009; Hauptman 2008). While the need for accuracy and ethical behavior are highly prized in the scientific disciplines, plagiarism is widespread in colleges and universities (Franklyn-Stokes & Newstead 1995; McCabe et al. 2001; DeVoss & Rosati 2002; Breen & Maassen 2005; Selwyn 2008), and studies show that it is particularly prevalent in science and engineering courses (McCabe 1997; Sheard et al. 2002; Simon et al. 2004; Yeo 2007). Plagiarism includes the copying or paraphrasing of another's words or ideas without appropriately crediting the original author (Eret & Gokmenoglu 2010) while it is the most commonly cited form of academic dishonesty at universities (Breen & Maasen 2005; Selwyn 2008). When asked why they plagiarized, students in the sciences often cite an inability to keep up with the heavy workload (McCabe 1997). Further complicating attitudes toward plagiarism are students steeped in the Internet culture who may not perceive plagiarism as problematic given the ease with which modern technologies facilitate these behaviors (Park 2003; Southworth 2015). Many science students view laboratory reports as somehow different from other types of writing and not subject to the same rules of source attribution. Higher incidences of plagiarism in science classes may also be due to difficulties reading and writing in a new genre. Articles in scientific journals are often filled with mathematical formulae and technical language that is difficult for students to understand and paraphrase (Yeo 2007).

Confusion about proper source attribution begins in the K-12 educational setting where instruction about plagiarism may be limited to running written work through an electronic detection program like Turnitin, and schools often lack standard policies, such as academic honor codes, that provide opportunities for those who plagiarize to receive proper remediation (McCabe & Katz 2009; Southworth 2015). Dant (1986) suggested that some high school teachers fail to discourage copying without attribution and a few may even endorse it. Of the college freshmen surveyed, 50% reported copying a majority of the material for high school assignments without penalty, 32% said that they didn't think citing sources within the text was necessary as long as they had a reference page, and 17% said that some of their high school teachers actually encouraged copying source materials for some assignments (Dant 1986). More recently, McCabe and Katz (2009) reported that 59% of high school juniors and seniors admitted to routinely copying source materials within the previous year. In a survey of high school students in ninth through twelfth grade, Sisti (2007) found that 35% admitted to copying and pasting material directly from the Internet. Only 46% percent of these students recognized this as cheating and they cited lack of time, preparation, interest, or consequences as reasons why they did it anyway (Park 2003; Sisti 2007). While many students undoubtedly know that it is unethical to copy material without attribution, many are confused about proper paraphrasing and how to cite sources. A study by Breen and Maassen (2005) showed that while most college students are concerned about avoiding plagiarism, they often lack the skills and understanding necessary to avoid doing so. In a study where college students were asked to identify plagiarism in writing samples, almost half of the students failed to do so correctly (Roig 1997).

Methods

In order to assess source citation among middle and high school students, research reports from two regional science fairs and one state science conference were evaluated. One of the regional science fairs surveyed receives student projects from 12 Georgia and eight South Carolina counties and the other from nine South Carolina counties. The science conference surveyed hosts high school students from across the state of South Carolina. According to science fair guidelines, projects submitted for judging at a regional fair must be accompanied by a written report (Society for Science & the Public 2012a). Students presenting at the state science conference had the option of including a written report to be judged as a separate event. Over 90% of the participants at this conference submitted a written report.

The regional science fair reports were surveyed on site. A limited amount of time was allowed for evaluation of the research reports so our rubrics had to be simple enough to allow for review of every 6th-12th grade report available at the fair. Due to issues of time and access, the authors were unable to address issues such as proper paraphrasing or copying material from the Internet, but focused instead on source attribution. Reports from the state science conference were borrowed for a short period of time from the judges of those reports. Not every report from the conference was evaluated and selection was based solely on the cooperation and availability of the individual judges. Two specific areas of the research reports were evaluated, in-text citations and reference page citations. The presence and adequacy of in-text citations within the background information of the paper was evaluated using the rubric in Table 1. The presence and completeness of citations in the reference page at the end of the report was evaluated using the rubric in Table 2. Wilson score intervals were calculated to compare differences between grade levels (Wilson 1927; Newcombe 1998).

Table 1

|

In-text Citations |

Level 0 |

No in-text citations are found in the introduction. |

Level 1 |

A majority of the information is NOT supported by in-text citations. |

Level 2 |

Approximately half of the information is supported by in-text citations. |

Level 3 |

A majority of the information is supported by in-text citations |

Table 1: In-text citations were ranked from zero to three based on the amount of information presented with an accompanying citation. | |

Table 2

|

Reference Citations |

Examples |

Level 0 |

No reference page is found at the end of the report. |

|

Level 1 |

A majority of the reference information is lacking in detail. |

1. John Smith |

Level 2 |

Some of the reference information is lacking in detail |

1. John Smith "Thermodynamics" 2005 |

Level 3 |

All information is detailed and present. |

Smith, J.M.; Van Ness, H.C., Abbott, M.M. (2005) Introduction to Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics. McGraw Hill, NY, NY. |

Table 2: Reference citations were ranked from zero to three based on how complete the reference was. A complete reference had information about the author, year, article title, and appropriate publication title, volume number or publisher. | ||

In addition to evaluating student research reports, science faculty at the universities hosting the science fairs were surveyed regarding their perceptions of what students do and should learn in high school about source use and citation. Faculty were presented with two questions regarding five specific citation activities and asked to rank them on a five point scale:

Citation Activities Surveyed:

- Citing sources within a paper (in-text citations)

- Citing sources on a reference page

- Paraphrasing source material

- Using standard citation styles (i.e. MLA, APA, CBE)

- Using journal articles as source materials

Questions/ Possible Responses:

- How familiar do you expect incoming freshman to be with the following (i.e. they practiced it in high school)?

They are well practiced and proficient

They had many practice opportunities

They had a moderate amount of practice

They had minimal practice

They have never practiced this - How important do you think it is for these activities to be practiced in high school?

Critically important

Very important

Somewhat important

Minimally important

Not at all important

Results

In-text Citations

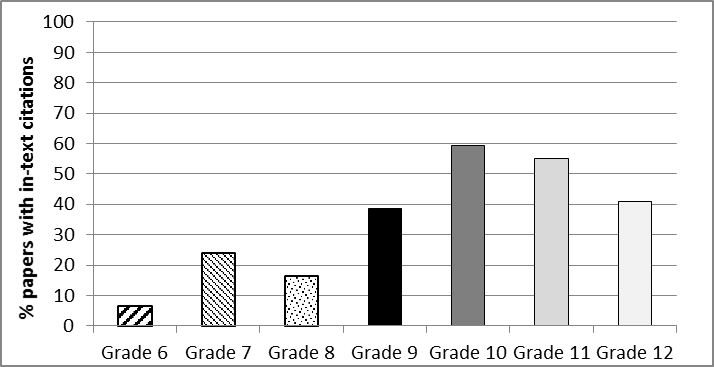

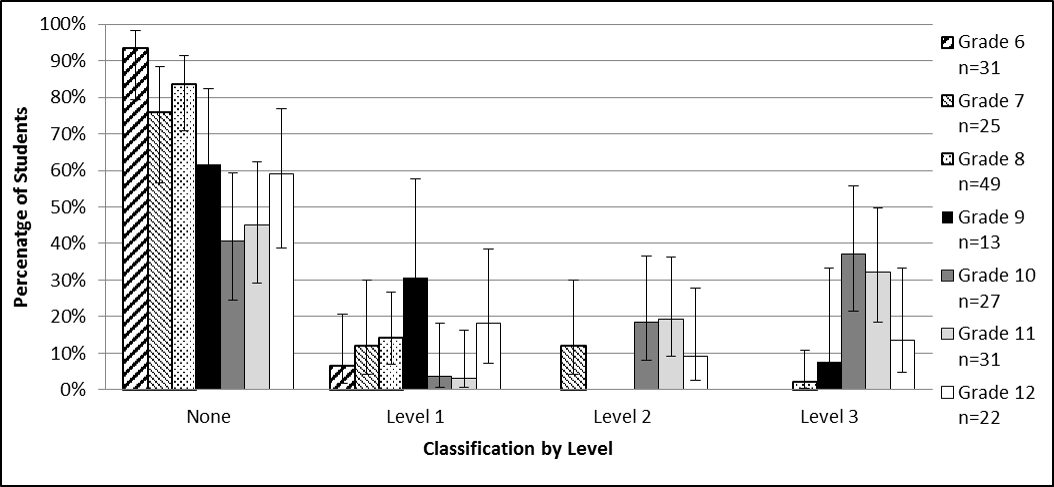

Less than a third of the surveyed reports submitted by 6th through 12th grade students had any in-text citations. Out of 198 total, only 32% (63) had in-text citations supporting their background information (Figure 1). Of those, 35% (22) of the reports were coded as level one (a majority of the information is not supported), 25% (16) were coded as level two (approximately half the information is supported) and 40% (25) were coded as level three (a majority of the information is supported) (Figure 2). Overall, the sixth grade (n=31) research reports had the least amount of in-text citation with only 6.5% (2) having them and both reports were coded as having only level one in-text citations.

Figure 1: Percentage of students with in-text citations per grade. (n=198)

There was an initial increase in the use of in-text citations as grades progressed with the highest use being represented by the tenth grade (n=27). Not only did the tenth grade have the highest percentage of in-text citation usage, 59% (16), but they also had the highest percentage of level three citations. Of the tenth grade reports with in-text citations, 6% (1) were classified as level one, 31% (5) were classified as level two and 63% (10) were classified as level three. After tenth grade, the percentage of students using in-text citations declines. For the twelfth grade (n=22) only 41% (9) of the reports had in-text citations and of these, 44% (4) were classified as level one, 22% (2) were classified as level two and 33% (3) were classified as level three.

Figure 2: Percentage of students in each grade with a given level of in-text citation competency.

Reference Citations

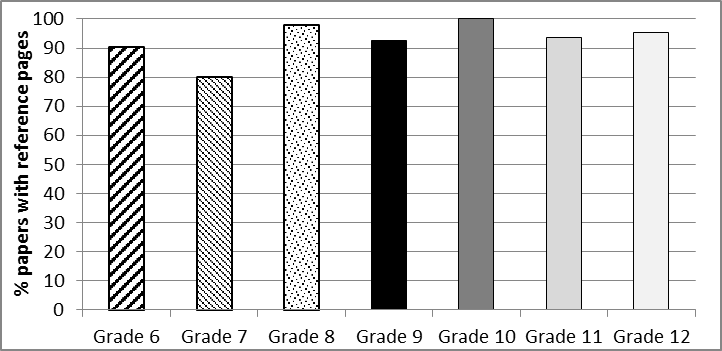

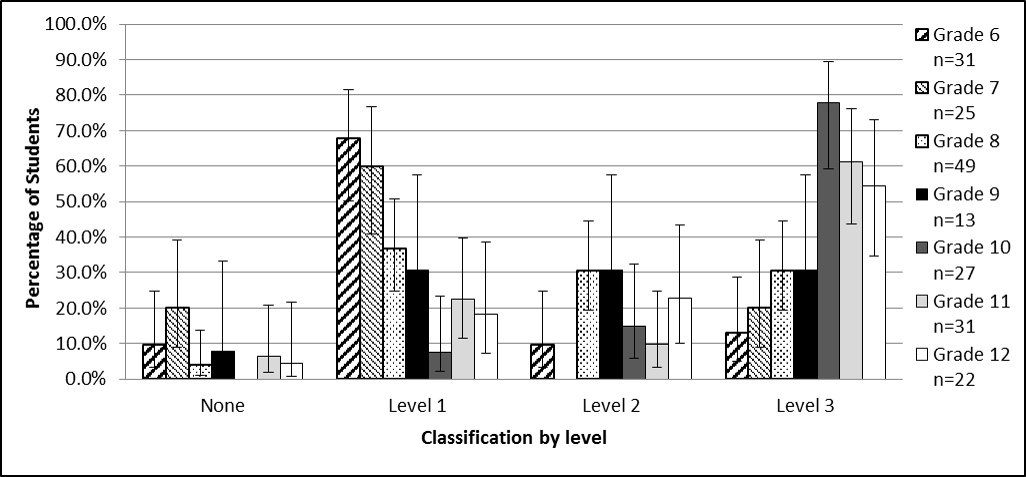

Overall, students in all grades were much better at providing reference pages in their reports, although many had trouble providing complete information in their references. Out of the 198 research reports surveyed, 93% (185) had reference pages attached (Figure 3). Of these, 38% (71) were coded as level one (a majority of the information is absent), 18% (34) were coded as level two (some of the information is absent) and 43% (80) were coded as level three (all information is present). (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Percentage of papers with reference citations by grade. (n=198)

The grade with the lowest percentage of reference page usage was the 7th (n=25). Only 80% (20) of the reports submitted by 7th graders had a reference page, compared to 90% (28) of the 6th grade reports. Although 90% of the 6th graders provided a reference page, they had the lowest percentage of level three references at 14% (4) and the highest percentage of level one references at 75% (21). The 10th grade had the highest percentage of reference page usage with 100% of their reports providing a reference page. Of these 10th grade reports, 7% (2) were coded as level one, 15% (4) were coded as level two and 78% (21) were coded as level 3. Once again, there is a decrease (although slight) after the 10th grade with 94% of 11th graders providing a reference page and 96% of 12th graders providing a reference page. Fewer 11th and 12th grade students, as compared to 10th grade, provide complete information however. By 12th grade only 57% of reference pages are coded as level 3.

Figure 4: Percentage of students in each grade level with source citations separated by type.

Faculty Survey

The results of the faculty survey (n= 23) show that 60% of university science faculty perceive that students have had at least moderate practice citing references on a reference page in their high school papers. Seventy-four percent perceive that students have had at least moderate practice paraphrasing sources for their papers. About a third of science faculty think students have had at least moderate practice using in-text citations (30%) and using a standard citation style (35%). Few think that students have at least moderate practice using journal articles as source materials (13%).

|

Proficient |

Many |

Moderate |

Minimal |

Never |

In-text citations |

0 |

1 |

6 |

13 |

3 |

Reference page |

1 |

4 |

9 |

6 |

3 |

Paraphrasing |

0 |

4 |

13 |

5 |

1 |

Citation styles |

0 |

1 |

7 |

8 |

7 |

Journal articles |

0 |

0 |

3 |

9 |

11 |

Table 3: Number of college science faculty who perceive students to have had a given amount of practice in high school with each citation activity. | |||||

When asked how important it is for high school students to practice each citation activity in high school the percentages go up. Over 95% of the science faculty surveyed felt that it is at least somewhat important for high school students to have practice providing a reference page, using in-text citations, and paraphrasing source material. Twenty-two percent of the faculty felt that practice using in-text citations and a reference pages was of critical importance. More than half of the faculty felt that practicing paraphrasing was critically important for high school students. Fewer faculty placed a high value on practicing standard citation styles or using journal articles as source materials.

|

Critical |

Very |

Somewhat |

Minimal |

Not at all |

In-text citations |

5 |

12 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

Reference page |

5 |

9 |

8 |

1 |

0 |

Paraphrasing |

12 |

10 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Citation styles |

1 |

6 |

12 |

1 |

3 |

Journal articles |

1 |

8 |

3 |

6 |

5 |

Table 4: Number of college science faculty that place a given amount of importance on practicing each citation activity in high school. | |||||

Discussion

Most studies of plagiarism use self-report methods rather than collection and assessment of written artifacts, and data at the middle and high school levels are particularly sparse; thus, this paper represents a significant contribution in this area. The self-report studies that have been done (i.e. Dant 1986; McCabe and Katz 2009, and Sisti 2007) focused mainly on the issue of copying, rather than paraphrasing or integrating, source material and not specifically on source attribution. While the methodologies and areas of focus are different, this study found the prevalence of plagiarism to be much higher than estimated previously, with more than 85% of high school seniors failing to provide adequate source attribution in their research reports. Given this finding, high school teachers, librarians, and college faculty may need to develop better, non-punitive instructional methods to teach and reinforce source attribution.

Observed Source Attribution and College Faculty Perceptions

It appears that students are receiving instruction about reference pages by at least the 6th grade and, in most cases, it seems that by high school students are receiving opportunities to practice and master complete reference citations. College faculty perceptions of what students practice in high school are likely influenced most directly by what their students have trouble with when writing college papers. The majority of college faculty surveyed felt that students had at least a moderate level of practice with reference pages and 61% felt that this is an activity that is very important or critical to practice in high school. While it appears that students are receiving adequate practice writing reference pages in high school, providing a reference page without understanding how this list of information must be linked to the text through the use of in-text citations misses a critical component of source attribution.

It appears that far fewer students are receiving adequate instruction or opportunity to practice proper in-text citation. Something may be happening by the 10th grade to foster the increased use of in-text citations because more than half of the 10th graders are using them to support the majority of their information; however this does not appear to be strongly reinforced in the 11th and 12th grade as there is a decline in the overall use of in-text citations in reports from these grades and fewer than 15% of the reports by high school seniors provided sufficient in-text citations. Only one of college faculty surveyed felt that students have had many opportunities to practice in-text citations and almost ¾ of them felt that this activity is very important or critical.

Although this investigation of science fair reports did not look at other activities important to proper source use and attribution, faculty were surveyed regarding these activities. Most reported that paraphrasing was very important or critical, yet only 17% felt that students are given many opportunities to practice it. Fewer faculty (30%) placed a very high value on the practice of different citation styles in high school. Because there are many citation styles specific to different academic disciplines, college faculty must introduce students to the citation style specific to their discipline as a typical part of college writing instruction.

Suggestions for Improvement

Based on state educational standards, students in both South Carolina and Georgia should be practicing in-text citations throughout high school, and the widely adopted Common Core State Standards require students to, "Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of science and technical texts" (ELA Standard, Science and Technical Subjects, Grade 11-12, 1) by the 12th grade (Common Core State Standards 2015; South Carolina Department of Education 2008; Georgia Department of Education 2006). Given these expectations widely set forth across state educational standards, why are so few students using in-text citations in their science fair reports? It is likely that students participating in science fairs are not receiving needed instruction or mentoring related directly to the written component of their project. Mentors may place most of the emphasis on experimental design/implementation and poster creation and less on effective written communication of results even though writing is an integral part of the scientific process.

Addressing this problem requires attention at two fronts; during the production and design process and as a component of the evaluation of the finished product. Effective written communication, including appropriate source attribution, needs to become a priority for everyone involved in the science fair at all levels. Effective instruction regarding adequate source attribution in the research report must be given when students are mentored through their science project. Mistakes should be addressed at the school level and revision should be encouraged before a student presents at a regional science fair. Judging at all levels should include an assessment of source attribution and it should be made clear to student participants that this is an area that will be considered when judging occurs. Students who do not properly credit their sources (including proper use of in-text citations) should be disqualified from winning awards. By continuing to reward students for producing reports that would be considered plagiarism at the college level, the science fair experience is reinforcing undesirable behaviors that may result in academic failure or even expulsion during their college careers.

Conclusions

Research-based writing is critical to practicing and learning about science (Yore et al. 2002; Yore et al. 2004; Glynn & Muth 2006). Based on the prevalence of plagiarism reported in the college classroom (Breen & Maasen 2005; McCabe 2005; Yeo 2007) and the results of this study, it appears that students are entering college unprepared to avoid academic dishonesty in their scientific writing assignments. This also speaks to the disconnect faculty in this study observe between student use of in-text citations and collegiate writing expectations. Whether this is due to high school students not being taught proper source attribution skills, not being remediated for papers lacking proper attribution, or even being rewarded for producing projects that lack proper source attribution, the students carry these habits with them into the college classroom. By presenting the prevalence of citation errors evident in middle and high school science fair research reports, this study hopes to encourage high school teachers, librarians, science fair officials, and mentors to provide more specific instruction on proper citation in scientific reports and across the disciplines. Improving emphasis on the source attribution practices of top high school science students will help the transfer of scientific skills, knowledge, and dispositions to the higher education environment and better prepare students for the strict academic integrity requirements of the academy.

References

American Association of School Librarians. 2007. Standards for the 21st Century Learner. Chicago, IL: American Library Association. Available from http://www.ala.org/aasl/sites/ala.org.aasl/files/content/guidelinesandstandards/learningstandards/AASL_Learning_Standards_2007.pdf

Association of College and Research Libraries. 2015. Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Chicago, IL: American Library Association. Available from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Breen, L. & Maassen, M. 2005. Reducing the incidence of plagiarism in an undergraduate course: The role of education. Issues in Educational Research. 15(1): 1-16. Retrieved from http://www.iier.org.au/iier15/breen.html

Common Core State Standards. 2015. English & Language Arts Standards for Science & Technical Subjects, Grades 6-12. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/RST/introduction/

Dant, D.R. 1986. Plagiarism in high school: A survey. The English Journal. 75(2): 81-84. doi: 10.2307/817898

DeVoss, D & Rosati, A.C. 2002. "It wasn't me, was it?" Plagiarism and the web. Computers and Composition. 19: 191-203. doi: 10.1016/S8755-4615(02)00112-3

Eret, E., & Gokmenoglu, T. 2010. Plagiarism in higher education: A case study with prospective academicians. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2:3303-3307. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.505

Franklyn-Stokes, A. & Newstead, S.E. 1995. Undergraduate cheating: Who does what and why? Studies in Higher Education. 20(2): 159-172. doi: 10.1080/03075079512331381673

Georgia Department of Education. 2006. English Language Arts (ELA) Standards. Retrieved from http://gadoe.georgiastandards.org/english.aspx.

Glynn, S.M. & Muth, K.D. 2006. Reading and writing to learn science: achieving scientific literacy. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 31(9): 1057-1073. doi: 10.1002/tea.3660310915

Harwood, N. 2009. An interview-based study of the functions of citations in academic writing across two disciplines. Journal of Pragmatics. 41: 497-518. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2008.06.001

Hauptman, R. 2008. Authorial ethics: How writers abuse their calling. Journal of Scholarly Publishing. 39:323-353. doi: 10.3138/jsp.39.4.323

Head, A.J. 2013, Dec. 5. Learning the Ropes: How Freshmen Conduct Course Research Once They Enter College. Seattle, WA: Project Information Literacy. Retrieved from {http://www.projectinfolit.org/uploads/2/7/5/4/27541717/pil_2013_freshmenstudy_fullreportv2.pdf}

McCabe, D. 1997. Classroom cheating among natural science and engineering majors. Science and Engineering Ethics. 3: 433-445. doi: 10.1007/s11948-997-0046-y

McCabe, D. 2005. It takes a village: Academic dishonesty and educational opportunity. Liberal Education. 91(3): 26-31.

McCabe, D., & Katz, D. 2009. Curbing cheating. Education Digest. 75(1): 16-19.

McCabe, D.L., Trevino, L.K., & Butterfield, K.D. 2001. Cheating in academic institutions: A decade of research. Ethics & Behavior. 11(3): 219-232. doi: 10.1207/S15327019EB1103_2

Newcombe, R.G. 1998. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: comparison of eleven methods. Statistics in Medicine. 17: 873-890. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<873::AID-SIM779>3.0.CO;2-I

Park, C. 2003. In other (people's) words: Plagiarism by university students - literature and lessons. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. 28: 471-488. doi: 10.1080/02602930301677

Roig, M. 1997. Can undergraduate students determine whether text has been plagiarized? Psychological Record. 47: 113-122. Retrieved from http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/tpr/vol47/iss1/7

Savannah River Site. 2012. Savannah River Regional Science and Engineering Fair. Retrieved from http://educationoutreach.srs.gov/srrsef.htm

Selwyn, N. 2008. Not necessarily a bad thing ...": A study of online plagiarism amongst undergraduate students. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. 33(5): 465-479. doi: 10.1080/02602930701563104

Sheard, J., Dick, M., Markham, S., McDonald, I. & Walsh, M. 2002. Cheating and plagiarism: perceptions and practices of first year IT students. Proceedings of the 7th Annual Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education. 183-187. doi: 10.1145/544414.544468

Simon, C.A., Carr, J.R., McCullough, S.M., Morgan, S.J., Oleson, T. & Ressel, M. 2004. Gender, student perceptions, institutional commitments and academic honesty: who reports in academic dishonesty cases? Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. 29(1): 75-90. doi: 10.1080/0260293032000158171

Sisti, D.A. 2007. How do high school students justify Internet plagiarism? Ethics & Behavior. 17(3): 215-231. doi: 10.1080/10508420701519163

Society for Science & the Public. 2012a. Intel International Science and Engineering Fair International Rules and Guidelines 2013. Retrieved from {https://web.archive.org/web/20130117213149/https://www.societyforscience.org/document.doc?id=396}

Society for Science & the Public. 2012b. Most Common Reasons for Projects to Fail to Qualify at Intel ISEF. Retrieved from {https://web.archive.org/web/20121102032541/https://www.societyforscience.org/page.aspx?pid=802}

Society for Science & the Public. 2008. 2010 Affiliated Fair Information. Retrieved from https://student.societyforscience.org/affiliated-fair-network.

South Carolina Department of Education. 2008. South Carolina Academic Standards for English Language Arts. Retrieved from http://ed.sc.gov/agency/programsservices/59/documents/StateBoardApprovedFinalMay14.pdf

Southworth, A.J. 2015. Plagiarism can be a learning opportunity. School Library Monthly. 31(4): 12-15.

Whitley, B.E. 1998. Factors associated with cheating among college students: A review. Research in Higher Education. 39: 235-274. doi: 10.1023/A:1018724900565

Wilson, E.B. 1927. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 22: 209-212. doi: x10.1023/A:1018724900565

Yeo, S. 2007. First-year university science and engineering students' understanding of plagiarism. Higher Education Research & Development. 26(2): 199-216. doi: 10.1080/07294360701310813

Yore, L.D., Hand, B.M., & Prain, V. 2002. Scientists as writers. Science Education. 86: 672-692. doi: 10.1002/sce.10042

Yore, L.D., Hand, B.M. & Florence, M.K. 2004. Scientists' views of science, models of writing, and science writing practices. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 41(4): 338-369. doi: 10.1002/tea.20008

| Previous | Contents | Next |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.