| URLs in this document have been updated. Links enclosed in {curly brackets} have been changed. If a replacement link was located, the new URL was added and the link is active; if a new site could not be identified, the broken link was removed. |

Science and Technology Librarians: User Engagement and Outreach Activities in the Area of Scholarly Communication

Lutishoor Salisbury

Distinguished Professor/Librarian

Head of the Chemistry and Biochemistry Library

University of Arkansas Libraries

Fayetteville, Arkansas

lsalisbu@uark.edu

Julie Speer

Associate Dean for Research and Informatics

University Libraries

Virginia Tech

Blacksburg, Virginia

jspeer@vt.edu

Abstract

This paper highlights the findings of a survey completed by ACRL/STS members on scholarly communication issues. In particular it identifies the percentage of their daily activities that are spent in support of scholarly communication activities; extent of change of job responsibilities in the last five years; roles engaged in relating to scholarly communication including those that are formal responsibilities, those they are informally engaged in, or those with which they have no engagement. It highlights areas in the area of scholarly communication that STS members need to know more about or want to know more about. It presents the status of open access policies at members' institutions and the needs expressed by members about activities that STS or ACRL could undertake to help advance their work in the areas of scholarly communication.

Background

In 2009, The Science and Technology Section (STS) of the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), a Division of the American Library Association (ALA) established an Open Access Task Force to identify open access issues of interest to science librarians with its charge "To address ongoing, critical work in open access and scholarly communication, and will specifically address the following related areas: education, communication, advocacy, collaboration and other emerging areas." (ACRL/STS Scholarly Communication Committee 2015)

The task force soon became a standing committee on scholarly communication and the group began efforts to implement tasks to advance open access and scholarly communication initiatives with and on behalf of STS. Five years later, in 2013, members of the committee planned a survey-based assessment to identify the state of scholarly communication interest and engagement among members of STS. It was hoped that the information gathered would be used to ensure alignment of any future work with current and communicated needs and expectations of members of the organization. Several significant advances in the national and global scholarly communication environment served as the impetus to survey the current librarian practice and level of understanding and engagement in scholarly communication. Among these are the February 2013 OSTP memo on public access to the results of federally funded research (Office of Science and Technology Policy 2013), NSF data management plan requirement (National Science Foundation 2011), and emerging tools and technologies that support access to, connections between, and interpretations of data and information. It was the consensus of the committee that the findings from the survey could be used to identify professional development needs to inform planning of appropriate training sessions in particular at midwinter and annual conferences of the American Library Association.

In order to meet one of the committee's objectives to pursue collaborative projects with other scholarly communication groups in and outside of ALA/ACRL, and recognizing that other professional library associations would likely have similar interests in disseminating a scholarly communication survey to their respective members, in 2014 the committee collaborated with the scholarly communication committees of ALA/ACRL's Education and Behavioral Sciences Section (EBSS) and the American Society for Engineering Education's (ASEE) Engineering Libraries Division (ELD) to design a joint scholarly communication survey.

The goals of the survey were to (a) demonstrate the degree to which changes in the scholarly communication ecosystem are translated into change at the operational levels for librarians, (b) to identify the challenges and assumptions about scholarly communication service activities, (c) to identify perceptions of, and attitudes towards, scholarly communication among members of ACRL/STS; ACRL/EBSS and the ASEE/ELD, and (d) to identify what members of these organizations see as emerging and pressing issues.

This paper reports on the findings of the survey from respondents who are STS members only. An overview of the findings of the survey responses from members of ACRL/STS; ACRL/EBSS and the ASEE/ELD will be published in a separate paper.

Specifically, this paper reports on the methods used; respondents' types of institutions; years of experience; their position within the organizations; the percentage of their daily activities that are spent in support of scholarly communication activities; extent of change of job responsibilities in the last five years; and roles engaged in relating to scholarly communication including those that are formal responsibilities, those they are informally engaged in, or those with which they have no engagement. It highlights areas that STS members need to know more about or want to know more about. It presents the status of open access policies at members' institutions and the needs expressed by members about activities that STS or ACRL could undertake to help advance their work in the areas of scholarly communication.

Methods

For the benefit of members taking the survey, the following expanded ACRL definition of scholarly communication was given at the beginning of the survey: "Scholarly communication encompasses the evolving systems and processes leveraged by scholars to use, reuse, document, share, preserve, curate, and measure the impact of new and traditional forms of scholarly communication. Datasets, publications (e.g. journal articles, books, book chapters, technical reports, and conference papers), software code, virtual research environments, blogs, and interactive digital scholarly resources are considered forms of scholarly communication and/or expression." (ACRL 2015).

In April 2015, a Qualtrics-based survey was sent to the STS mailing list requesting members to complete the survey. Virginia Tech's Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the survey instrument. Follow-up e-mails were sent in two-week intervals. As the STS mailing listis open to non-members, responses to the survey were requested only if the respondent was a member of STS section. The survey instrument consisted of 13 questions listed in Appendix 1. The questions were based on the expertise of the paper authors and members of the scholarly communication committees involved in the project. Respondents were not required to answer each question.

Results and Discussion

One hundred and fifty seven responses were received from STS members. This is a response rate of 12.5 percent; at the time of the survey STS had 1,251 members.

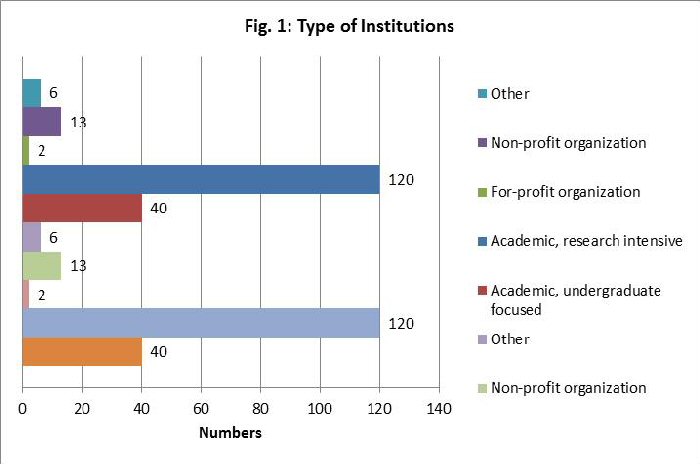

(a) Institution Type

One hundred and eighty one responses were recorded indicating that some respondents identified with more than one type of institution. The largest number of replies indicated that they belong to Academic, Research Intensive Organizations, this is followed by Academic Undergraduate Focused, then Non-Profit, For-Profit and other. The institutions identified under Other include academic medical (n=2); academic professional, or academic research (non-intensive) (n=2) and one each public university and government (See Fig. 1).

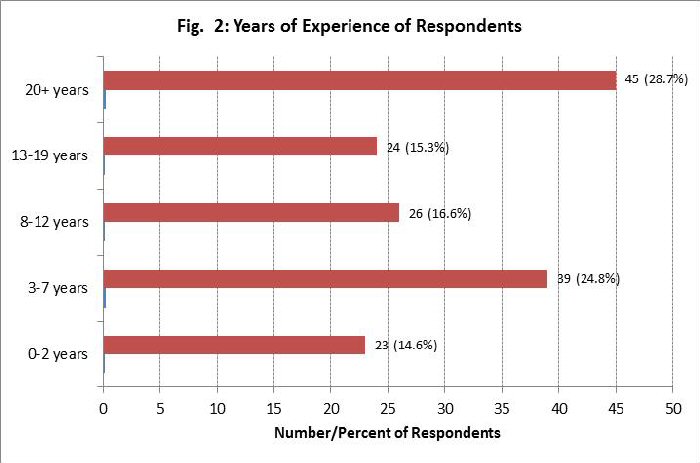

(b) Years of Experience

Respondents reported a range of years of experience in their jobs. (Fig. 2).

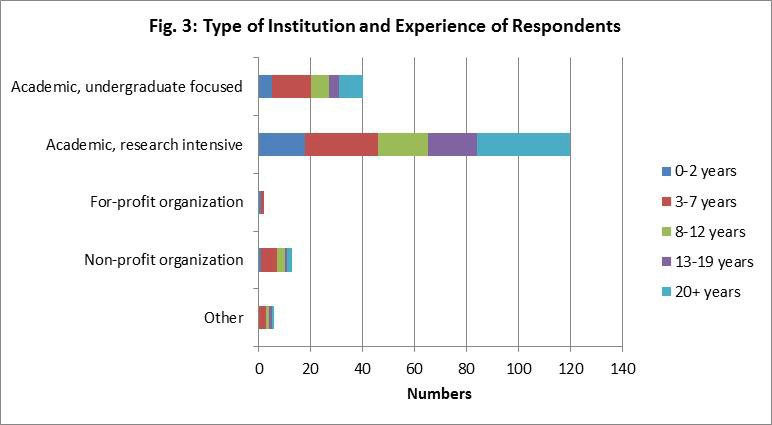

Most of the respondents in every experience group are situated in Academic Research Intensive Institutions, followed by Academic Undergraduate focused and then Non-profit organizations (see Fig. 3). All respondents in the For-profit Institution have less than 7 years of experience. Of the personnel in the Academic Research Intensive Institutions (n=120), the largest percent of them (30 percent) have more than 20+ years of experience, followed by 3-7 years with 28 percent, then 0-2 years with 18 percent, followed with equal percentage (19 percent) in the groups with 8-12 and 13-19 years.

Of personnel in the Academic, Undergraduate Focused Institutions (n=40), the largest percent of them (15 percent) have 3-7 years of experience, followed by the 20+ experience (9 percent), then 8-12 years (7 percent), followed by 0-2 years (5 percent), then 13-19 years (4 percent). The large number of respondents for the Non-profit organization is in the 3-7 years (46.2 percent) followed by 8-12 years (23 percent), then 20+ years (15.4 percent).

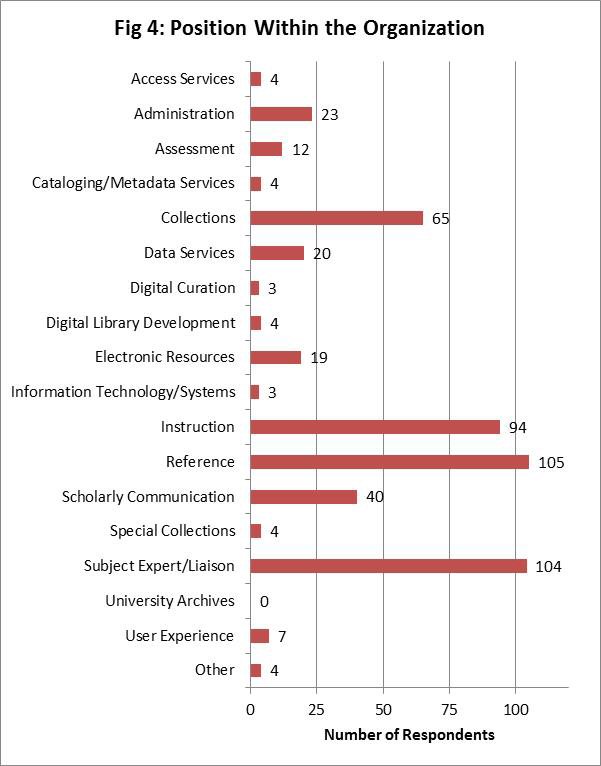

(c) Respondents' Positions in the Organization

Respondents were given 18 categories of possible programs/units/departments in a library organization. They were asked to identify how their position was situated in the library organization in relation to these categories. They were instructed to identify all the categories that apply to their position. Many respondents indicated that they support more than two roles (See Fig. 4). This result suggests that STS members function in various roles in libraries, which might also explain the range of needs expressed for information relating to scholarly communication issues. Most of the respondents (71.5 percent) identified themselves as being in the more traditional roles (collections, instruction, reference, and subject expert/liaison) typically performed by subject librarians or departmental liaisons. The highest number of respondents (n=105) were positioned in reference, followed by subject expert/liaison (n=104), instruction (n=94), collections (n=65), scholarly communication (n=40), administration (n=23), data services (n=20), electronic resources (n=19), assessment (n=12), while all other categories (access services [n=4], cataloging/metadata services [n=4], digital curation [n=3], digital library development [n=4], other [n=4], special collections [n=4] and user experience [n=7]) account for 33 of the responses.

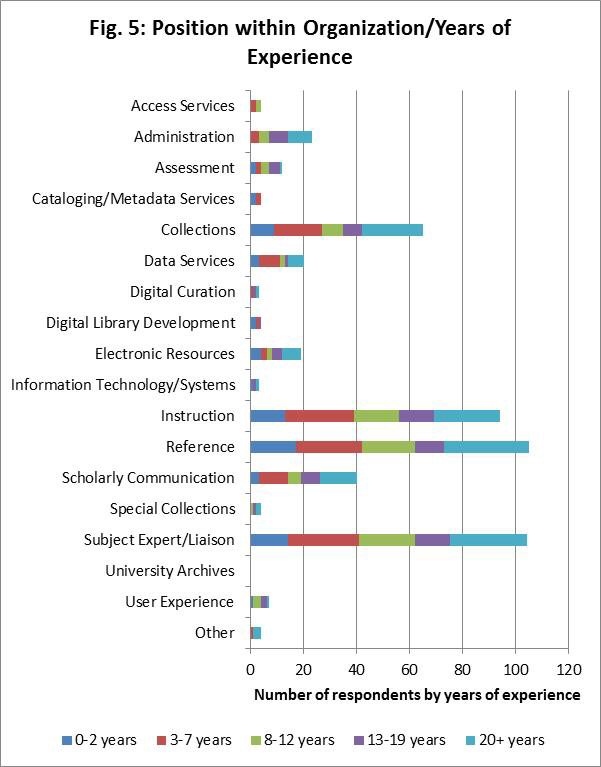

(d) Respondents' Positions in the Organization; Years of Experience or Types of Organizations

Figure 5 shows that a prevalence of responses with experience of 20+ years in the organizational areas with high response rates as: reference (n=32), subject expert/liaison (n=29), instruction (n=25), collections (n=23), and scholarly communication (n=14). This is followed by experience in the range of 3-7 years in the organizational areas with high response rates: (subject expert/liaison (n=27), instruction (n=26), reference (n=25), collections (n=18) and scholarly communication (n=11). Of the respondents who reported that their position is in scholarly communication (n=40), 35 percent of them have 20+ years of experience and 65 percent of them have more than 8 years of experience, most likely indicating a shift in job responsibilities into this area. Less than one percent (n=3) have between 0-2 years of experience. This suggests that experienced science and technology librarians are being positioned to serve as scholarly communication librarians, possibly at the campus wide level and or in roles that support faculty, staff, and student in scholarly communication activities at the departmental level. Of the respondents who reported that their position is in scholarly communication (n=40), 65 percent also reported serving in a subject expert/liaison role. This finding suggests that not all members of STS working in the scholarly communication areas are serving as subject experts/liaisons in their respective organizations.

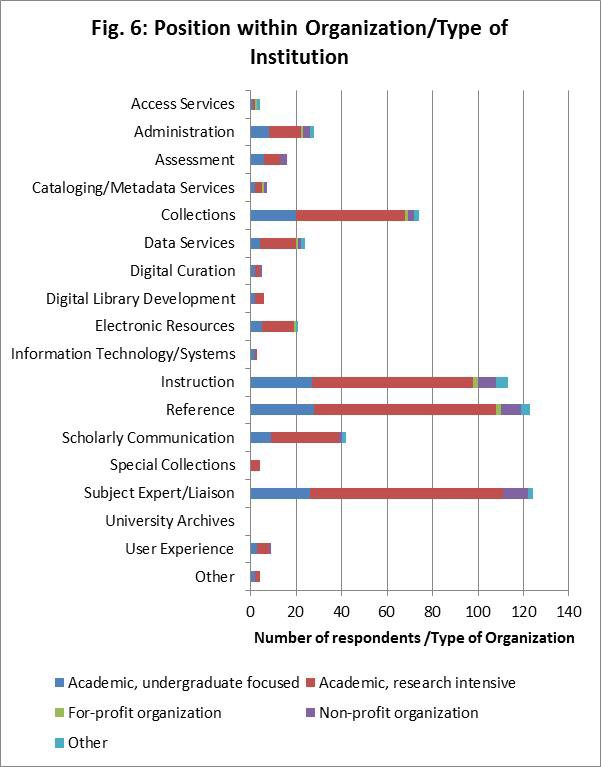

As shown in Fig 6, the majority of the respondents identifying themselves as subject expert/liaison are from academic research intensive schools (n=84), followed by academic, undergraduate focused (n=26), and non-profit (n=11). This is the same pattern followed for: Reference (academic, research intensive (n=80), academic, undergraduate (n=28) and non-profit (n=9); Instruction (academic, research intensive (n=71), academic, undergraduate (n=27) and non-profit (n=8); collections (academic, research intensive (n=48), academic, undergraduate (n=20) and non-profit (n=3).

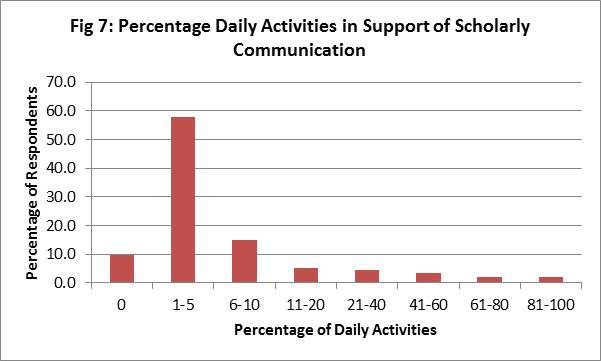

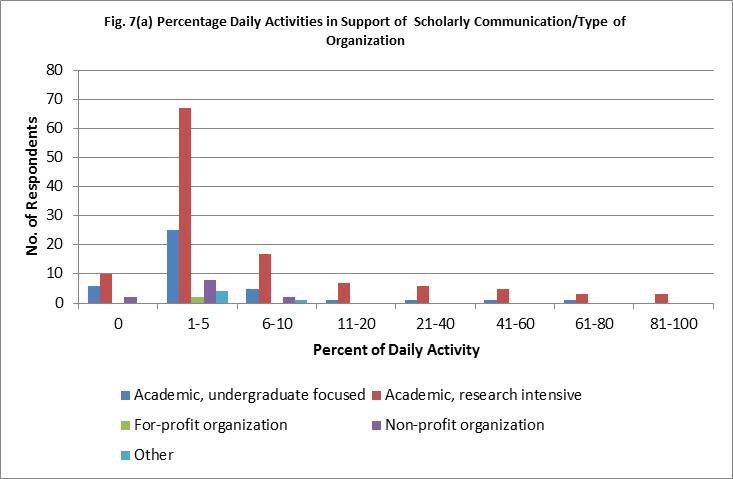

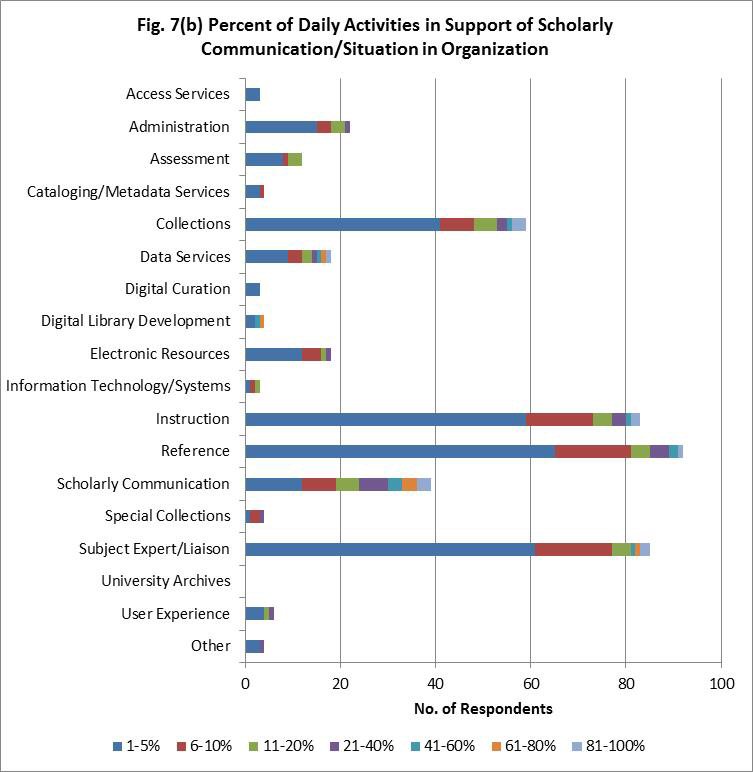

(e) Percentage of Daily Activities in Support of Institution's Scholarly Communication Activities

Of the 152 responses to this question, 15 do not support these activities on a daily basis, 88 support these activities between 1 and 5 percent, 23 between 6 and 10 percent, 8 between 11-20 percent; and 7 between 21-40 percent. Only 11 of the respondents support scholarly communication in more than 40 percent of their daily activities (See Fig.7). These data imply that the majority of STS members have integrated some aspect of scholarly communication activities in their daily activities. As was expected, most of these changes in activities are from respondents in Academic, Research Intensive institutions. (See Fig. 7(a). The areas where respondents spend more than 20 percent of their daily activities in support of scholarly communication activities are: Scholarly communication (n=15), followed by Subject Expert/Liaison (n=8), Reference (n=7), Instruction (n=6), Collections (n=5) and Data Services (n=4). (See Fig 7(b)).

It is interesting to note that for the 18 respondents who reported spending more than 60 percent of their actual day-to-day activities relating to scholarly communication, 6 of them are working in scholarly communication, 3 are subject expert/liaison, 3 in collections, 2 each in instruction and in data services, 1 each in digital library development and in reference.

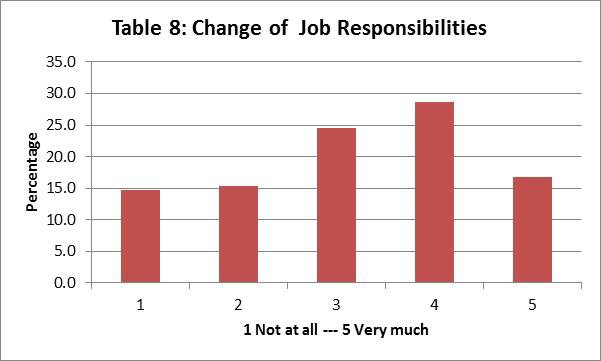

(f) Extent of Change of Job Responsibilities in the Last Five years

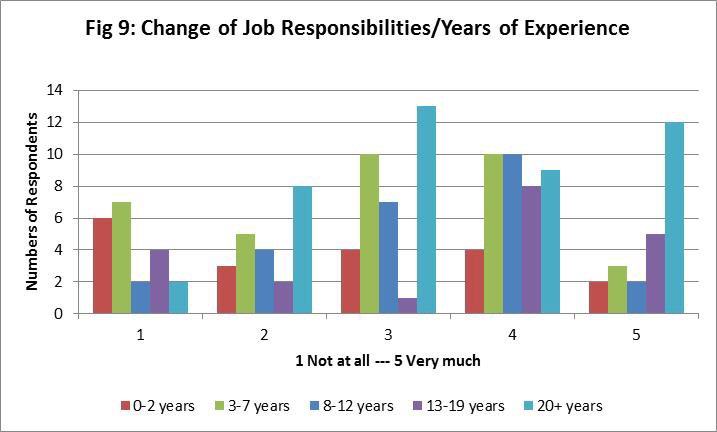

Respondents were asked to identify on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) how their job responsibilities have changed as a result of changes in scholarly communication. One hundred and forty three responses were received for this question. The job responsibilities for 15 percent (n=21) of the respondents did not change at all, indicating that 85 percent had some change. Forty percent (n=65) indicated either a 4 or 5, implying that their job responsibilities had changed substantially in support of scholarly communication activities (see Fig. 8).

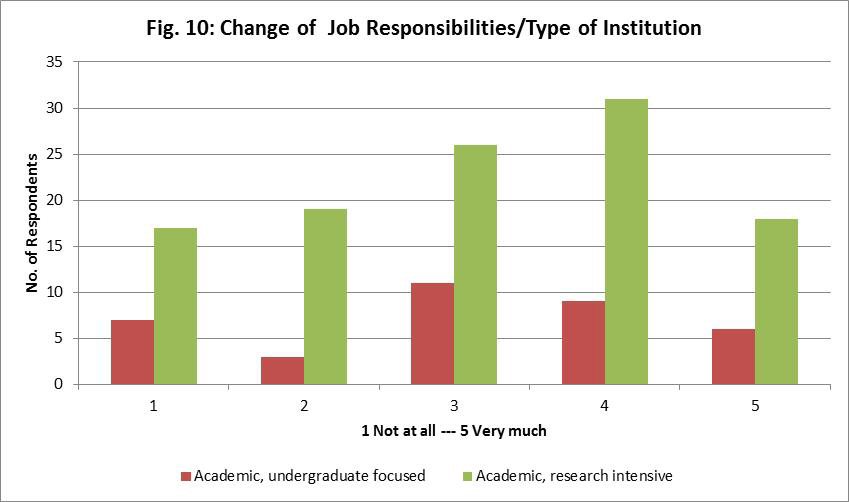

The change of job responsibilities was most prevalent among the respondents with more than 8 years of experience with the highest of those with 20+ years. Most of the change of responsibilities occurred in academic, research intensive institutions, followed by academic, undergraduate institutions (Figs. 9 and 10). It seems that the average change is uniform among all range of experience.

Role Engaged in Relating to Scholarly Communication

Twenty seven roles/activities were listed in the questionnaire and respondents were asked to identify whether it is (1) a formal responsibility; (2) an activity they are informally engaged in ; (3) an activity they need to know more about for their job; and (4) an activity they would like to learn more about for professional development. Respondents were asked to identify all that applied.

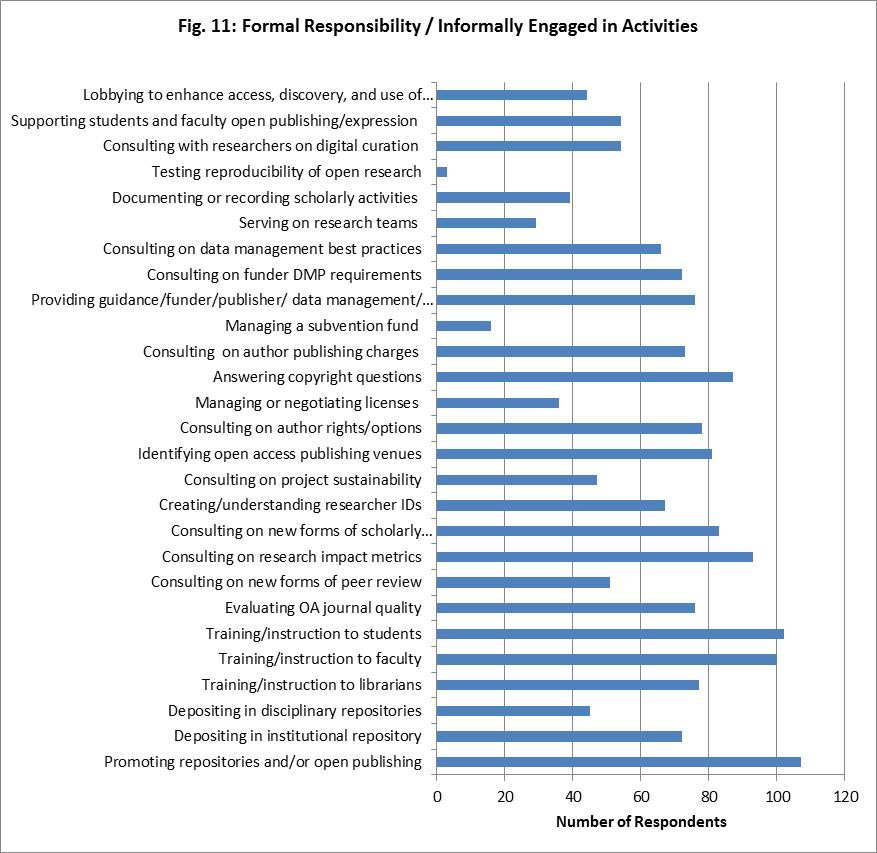

(a) Formal Responsibility/Informally Engaged

One thousand, seven hundred and twenty eight responses reported that they are involved with the activities as a formal responsibility or are informally engaged in one or more of the 27 role/activities listed (Fig 11). The results indicate that not all roles/activities surveyed are pervasive among librarians/information professionals who are STS members. Activities for which respondents indicated there was no engagement may still be in the planning stages or may be performed by some other part of the organization.

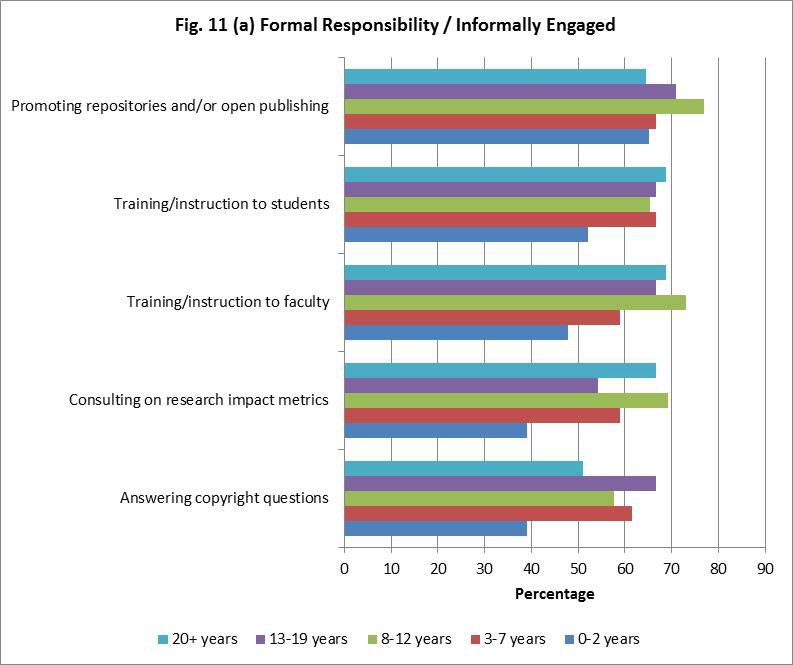

The top five activities that they are involved in are: promoting institutional or disciplinary repositories and/or open publishing (n=107), providing training/instruction to students on scholarly communication issues (n=102); providing training/instruction to faculty on scholarly communication issues (n=100); consulting with researchers on research impact metrics (n=93) and answering copyright questions (n=87). The activities with the least number of responses to 'formal' or 'informal' engagement include managing a fund for subsidizing the article processing charges of open access publications (n=16) and testing reproducibility of open research (n=3). The percentage of librarians/information worker within a particular age range who responded and their involvement with in the top 5 role/activity in the area of scholarly communication are shown in Fig. 11 (a). A slightly larger percentage of respondents in the 8-12 years seem to be heavily involved in the top five activities.

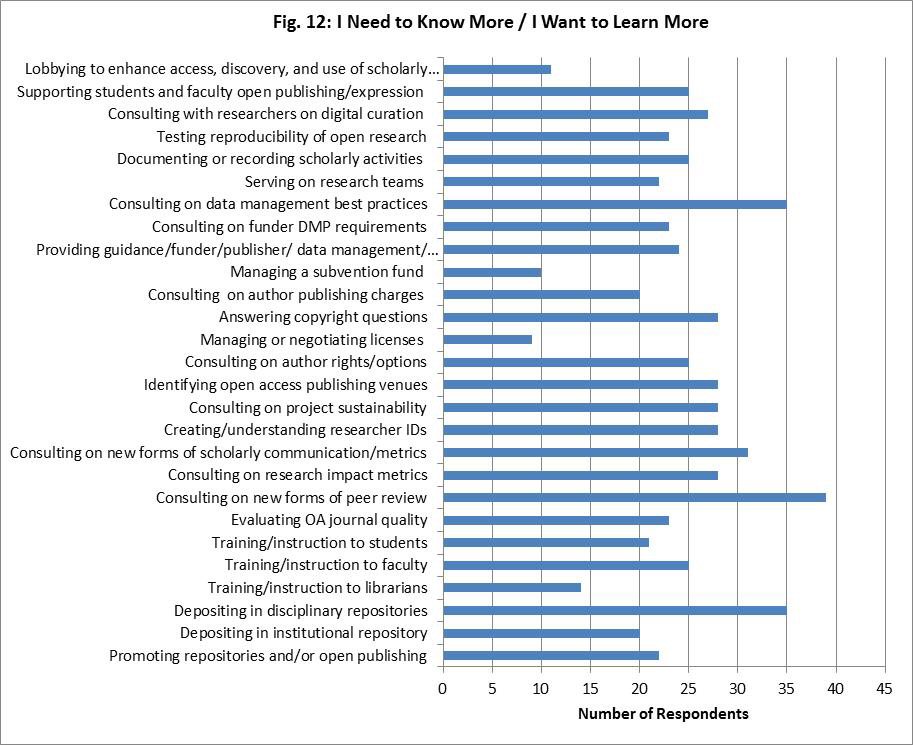

(b) Need to Know More / Want to Know More

Six hundred and forty nine responses reported that they need to know more or want to learn more in one or more of the 27 role/activities that were listed (Fig 12). The results indicate that even though formal/informal engagement in activities surveyed are not overwhelmingly widespread among STS members, the responses also indicate that there is not much interest in learning about some of these roles/activities. This may be because they: 1) believe they know enough about some of these roles/activities, 2) have no plans to assume more scholarly communication responsibilities, 3) do not believe some of the activities relate to their current job, or 4) these tasks are performed in another department in the organization.

The top five activities that respondents indicated that they need or want to know more about are: consulting with researchers on new forms of peer review (n=39), depositing materials in disciplinary repositories (n=35); consulting with researchers on data management best practices (n=35); consulting with researchers on emerging forms of scholarly communication and their metrics (n=31). Five activities tied at 28 responses for the fifth activity: consulting with researchers on research impact metrics, creating research IDs and/or understanding researcher ID options, recommending approaches to sustainability for scholarly publishing/expression projects, identifying open access publishing venues, and answering copyright questions. It is interesting to note that answering copyright questions-- is identified both as one of the top five formal/informal engagement activities, as well as, one of the top five activities respondents want to learn more about. This may be explained by the complex nature of most copyright questions and the need to follow case law in order to address them.

The activities with the least number of responses to 'need to know more' or 'want to learn more' include: managing or negotiating licenses for research/teaching (n=9) and managing a fund for subsidizing the article processing charges (n=10). The responses may be lower in these areas because other individuals may have responsibility for the activities, there may be no related service at the respondent's institutions, or the activity may not be perceived as high priority by the respondent or by their institution.

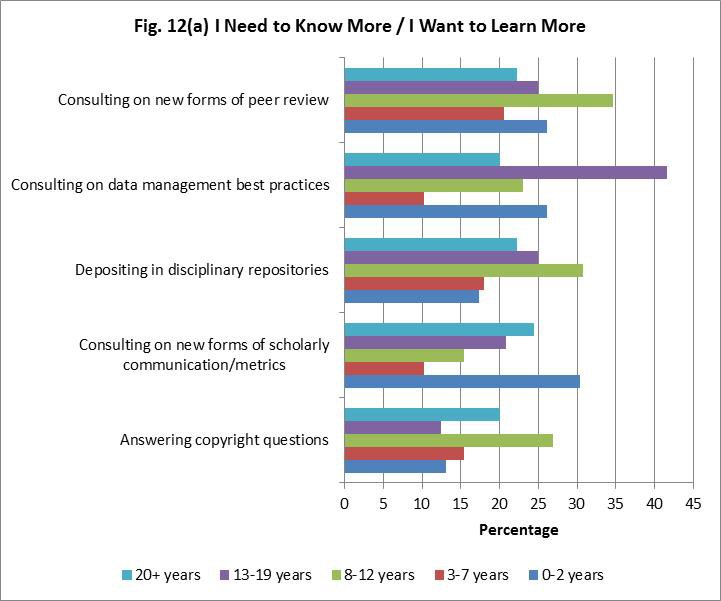

Fig 12(a) indicates the desirability to know more or want to learn more in the top five activity areas cross-referenced by the number of years of experience. Respondents within all range of experience want more about the top five areas but most want to learn about consulting on new forms of peer review. Most of the respondents in 8-12 years of experience feel that they need to know more/want to learn more in these top five areas, this is followed by those in the experience range of 13-19 years, 0-2 years, 20+ years and 3-7 years. Most of the respondents in the 0-2 years of experience want to learn about promoting repositories or open publishing and on consulting on data management best practices.

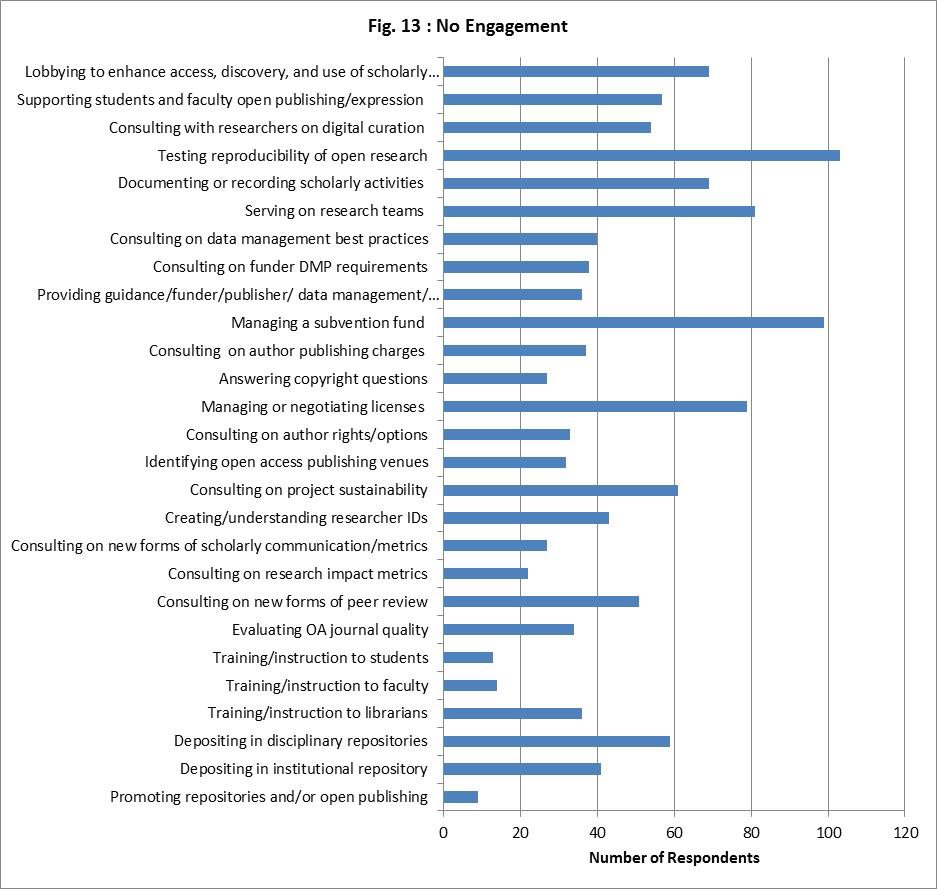

(c) No Engagement

One thousand, two hundred and sixty four responses indicated that they have no involvement in one or more of the 27 role/activities that were listed (Fig 13).

The top 5 activities for which respondents indicated that they have no engagement are: testing reproducibility of open research (n=103); managing a fund for subsidizing the article processing charges of open access publications (n=99); serving on research teams (e.g. systematic reviews, developing tools and/or research environments) (n=81); managing or negotiating licenses for research/teaching use of library resources (n=79) and documenting or recording scholarly activities (n=69).

The question specifically asked to consider the librarian's role/activity as it related to their current position and these activities may not be the direct responsibility of the individuals who answered the questionnaire. To gather the true extent of the librarian's involvement, the question should have specified whether the respondent was aware that these activities are being done by another individual in the library or the responsibility of another unit in the university.

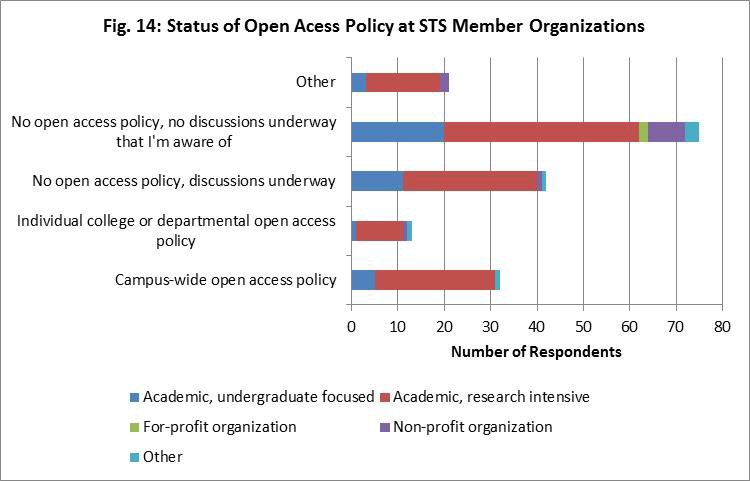

Status of Open Access Policy at STS Member Organizations

One hundred and eighty three responses were received to the question asking respondents to select the best description relating to open access policy at their institutions.

Of these respondents, 32 of them have a campus-wide open access policy; 13 have an individual college or departmental open access policy; 42 have no open access policy but discussions are underway and 75 have no open access policy, no discussions underway of which the respondents were aware.

When this information is compared to the types of organization responses (n=183), only 36 of the academic intensive research organizations have either a campus-wide open access policy or an individual college or departmental open access policy (See Fig 14).

The fact that only 41 of the respondents' institutions have either a campus-wide open access or a department policy may help to explain the small shift of librarian's responsibilities and formal roles assigned when dealing with scholarly communication issues. Nevertheless, it is heartening to learn that 42 more institutions have recognized the need and have discussions underway. Six academic undergraduate focused institutions either a campus-wide open access policy or an individual college or departmental open access policy. Eleven have discussions underway.

Needs Expressed

A range of needs were expressed in the free responses. Among these are: request for a more comprehensive definition of scholarly communication that defines the roles that are involved; identify the pieces that are needed to make it to work together with the basic knowledge and skill sets that are essential; provide pragmatic guidance on how to establish a meaningful service; a how-to integrate scholarly communication in daily workflow and do it well; evaluative criteria by which to assess success; provide guidance on best practices for teaching scholarly communication issues to faculty and students and provide evaluative criteria. Some respondents requested guidance such as scholarly communication 101 sessions that are not time intensive or costly. Others requested information on scholarly communication issues beyond the 101 level. Several requests were made for scholarly communication awareness that is specific to disciplines.

How STS Can Help

Several suggestions were given on how STS could assist members in bringing attention to scholarly communication issues at their organizations. These include providing self-study material and online training modules, organizing relevant workshops/webinars on various activities, arranging sessions at the ALA annual and mid-winter conferences, soliciting members to write about issues on scholarly communication topics in Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship as well as in College and Research Libraries. It was also recommended that a central Frequently Asked Questions be developed with recommended links to useful material.

Conclusion

The findings from the survey demonstrated that many of the activities listed in this survey are not the responsibility of the majority of librarians who responded to the survey. Most of the activities with high response rates were performed by reference, instruction, subject liaisons or collection librarians. The lack of engagement in some of the activities listed may be because fewer individuals with these responsibilities are members of STS or because STS is primarily comprised of science librarians. Future studies could compare survey results to STS membership data, for example, to compare the number of non-science liaison librarians STS members to the number of non-subject expert/liaison respondents to determine whether the data is truly representative of STS membership.

The data appears to suggest that librarians involved in reference, instruction, collection, and liaison activities are integrating scholarly communication related activities into their work. As they interact with and support faculty and student research, they may have opportunities to introduce new concepts and services during regular learning and research service activities. It is not surprising to see more engagement among respondents is in fairly well established library scholarly communication roles: promoting repository services, teaching scholarly communication topics to faculty and students, and providing copyright assistance. This could be explained by the similarities to roles that librarians with liaison responsibilities typically perform in supporting the information needs of their constituents: promoting new services, instruction, and research consultation. Less surprising is that the least amount of engagement is in areas that are fairly new to libraries or where professional standards, best practices, and roles are less clearly defined, such as testing the reproducibility of open research and documenting and recording scholarly activities. Because the majority of responses (n=368; 71.5 percent) to the question about where their position was situated in their organization were in traditional liaison areas: reference, instruction, subject expert/liaison, and collections, there may be little engagement in areas such as managing a subvention fund or negotiating licenses to support research and teaching because these areas are overseen by others in their organization or no related services may be offered at their institution. The findings helped to identify new scholarly communication topics of interest for midwinter and annual programs and for continuing education in this area.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank members of the ACRL/EBSS Scholarly Communication Committee, ACRL/STS Scholarly Commication Committee, and the ASEE/ELD Scholarly Communication Committee for their useful input to the development of the survey instrument.

References

ACRL. 2015. Scholarly Communication Defined. [Internet]. Available from http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/principlesstrategies

ACRL/STS Scholarly Communication Committee. 2015. Charge. [Internet]. Available from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sts/acr-stsscholar

National Science Foundation. 2015. Data Management Plan Requirements. [Internet]. Available at http://www.nsf.gov/bfa/dias/policy/dmp.jsp

Executive Office of the President. Office of Science and Technology Policy. 2013. Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies. [Internet]. Available from {https://web.archive.org/web/20161020065541/https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/ostp_public_access_memo_2013.pdf}

Appendix 1

Q1. Select the best description of the open access policy situation at your institution from the list below: (An open access policy is a policy in which authors grant their institution permission to make their work available publicly for educational purposes free of charge)

Options: Campus-wide open access policy; Individual college or departmental open access policy; No open access policy, discussions underway; No open access policy, no discussions underway that I'm aware of; Other

Q2. Which group or groups are you a member of? (check all that apply)

Options: ACRL Science and Technology Section; ACRL Education and Behavioral Sciences Section; ASEE Engineering Libraries Division

Q3. How long have you been information professional?

Options: 0-2 years; 3-7 years; 8-12 years; 13-19 years; 20+ years

Q4. How would you describe your institution? (check all that apply)

Options: Academic, undergraduate focused; Academic, research intensive; For-profit organization; Non-profit organization; Other

Q5. How is your position situated within your organization? (check all that apply)

Options: Access Services; Administration; Assessment, Cataloging/Metadata Services; Collections; Data Services; Digital Curation; Digital Library Development; Electronic Resources; Information Technology/Systems; Instruction; Reference; Scholarly Communication; Special Collections; Subject Expert/Liaison; University Archives; User Experience; Other

Q6. Which disciplines do you support? (check all that apply) (Note: question displayed for participants who selected subject expert/liaison in Q5)

Options: Aerospace Engineering; Engineering/Biosystems Engineering; Astronomy; Biology; Biomedical Engineering and/or Bioengineering; Business; Chemical Engineering; Chemistry; Civil Engineering; Computer Science/Computer Engineering; Education; Electrical Engineering; Environmental Engineering; Environmental Science; Geography; Geology; Humanities; Industrial Engineering; Interdisciplinary Studies; Materials Science; Mathematics; Mechanical Engineering; Nursing; Oceanography; Pharmacy; Physics; Plant Sciences; Psychology; Public Health; Social Work; Statistics; Urban Planning; Veterinary Medicine; Water Resources; Women's Studies; Other

Q7. What percentage of your actual day-to-day activities is in support of your institution's scholarly communication?

Options: 0%; 1-5%; 6-10%; 11-20%; 21-40%; 41-60%; 61-80%; 81-100%

Q8. What percentage of your actual day-to-day activities is in support of your departments' scholarly communication? (Note: question displayed for participants who selected subject expert/liaison in Q5)

Options: 0%; 1-5%; 6-10%; 11-20%; 21-40%; 41-60%; 61-80%; 81-100%

Q9. To what extent have your responsibilities as a librarian changed over the last 5 years as a result of changes in scholarly communication?

Options: Likert scale 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 – 1 (Not at all) : 5 (Very Much); Please explain.

Q10. To what extent has demand for scholarly communication services increased?

Options: Likert scale 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 – 1 (Not at all) : 5 (Very Much); Please explain.

Q11. For the following questions, please consider each librarian role/activity as it relates to your current position and whether: 1) it is a formal responsibility, 2) it is an informal activity (not a formal responsibility), 3) you need to know more for your position, or 4) you would like to learn more for professional development. (Note: Questions refer to activities in which you may have been engaged within the last two years. Engagement may have been on your own or as a member of a library committee.)

Options for Activities Listed Below: Formal Responsibility; Informally Engaged in Activities; No Engagement; I Need to Know More; I Want to Learn More

- Activity: Promoting institutional or disciplinary repositories and/or open publishing

- Activity 1: Depositing materials in an institutional repository

- Activity 2: Depositing materials in disciplinary repositories

- Activity 4: Providing training/instruction to librarians on scholarly communication issues

- Activity 5: Providing training/instruction to faculty on scholarly communication issues

- Activity 6: Providing training/instruction to students on scholarly communication issues

- Activity 7: Evaluating quality of scholarly open access journals

- Activity 8: Consulting with researchers on new forms of peer review (e.g. open peer review)

- Activity 9: Consulting with researchers on research impact metrics

- Activity 10: Consulting with researchers on emerging forms of scholarly communication and their metrics

- Activity 11: Creating research IDs and/or understanding researcher ID options (including ORCID, ResearcherID, Scopus Author Identifier)

- Activity 12: Recommending approaches to sustainability for scholarly publishing/expression projects

- Activity 13: Identifying open access publishing venues

- Activity 14: Consulting with researchers on author rights issues and publication licensing options (e.g. Creative Commons licenses)

- Activity 15: Managing or negotiating licenses for research/teaching use of library resources

- Activity 16: Answering copyright questions

- Activity 17: Consulting with researchers on author publishing charges (e.g. subvention funds, publisher voucher tokens, membership reduced rates, subscription reduced rates, institutional subscription reduced rates)

- Activity 18: Managing a fund for subsidizing the article processing charges of open access publications

- Activity 19: Providing guidance to researchers on funder, publisher, and/or institutional data management and sharing policies

- Activity 20: Consulting with researchers on funder data management plan requirements (e.g. consults on NIH and/or NSF data management plans)

- Activity 21: Consulting with researchers on data management best practices

- Activity 22: Serving on research teams (e.g. systematic reviews, developing tools and/or research environments)

- Activity 23: Documenting or recording scholarly activities (e.g. helping researchers gain credit for their contributions, documenting research processes and workflows for reproducibility purposes)

- Activity 24: Testing reproducibility of open research

- Activity 25: Consulting with researchers on digital curation (i.e. managing the lifecycle of digital information from creation through to preservation and sharing)

- Activity 26: Supporting students and faculty open publishing/expression (e.g. offering services for journal publishing, conference proceedings publishing, Open Educational Resources, digital projects)

- Activity 27: Lobbying with publishers and/or vendors to enhance access, discovery, and use of scholarly materials

Q12: What else would you like to share with us about your experience with, and interest in, scholarly communication issues and service activities? (This information will be used to inform the development of initiatives and programs that support interest in scholarly communication among the membership of each of our organizations)

Q13: What role would you like to see STS, EBSS, or ELD play in helping you better understand scholarly communication issues?

| Previous | Contents | Next |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.